Bacteria-Killing Viruses to Help Developing Countries Fight Cholera

-

-

Slice of MIT

Filed Under

“As a scientist, I always thought that if I develop something innovative, it will affect a whole community,” says Minmin “Mimi” Yen ’11, who was awarded a Howard Hughes Medical Institute fellowship as a grad student and who worked on translating bench science to clinical applications.

But when she flew to Haiti in 2014 to study the cholera epidemic, she realized the path to impact wasn’t so simple. “I realized some things get stuck in the lab. I saw people lined up waiting for hours to see one doctor. And many were very sick. I realized in startups people talk a lot about innovation, but the people who really need the attention often don’t get it.”

Two years after returning from Haiti, Yen launched her own effort. Now she’s cofounder and CEO of PhagePro, a biotech startup based in Boston that develops bacteriophages—viruses that target and kill specific bacteria—to fight diseases like cholera. The company, she says, aims to make its discoveries available to those who often don’t get the help they need.

Cholera is spread mainly through contaminated water sources because of inadequate sanitation, and it affects millions. Globally, there are at least 3 million cases of cholera each year and some 120,000 people die from it, according to the World Health Organization. In addition to Haiti, cholera outbreaks in recent years have hit Bangladesh, Mozambique, and Yemen. War or natural disasters often cause shortages of clean water, Yen says.

PhagePro’s approach is unique, Yen says, in that it is laying the groundwork to support low- and middle-income countries in fighting outbreaks themselves, rather than relying on charitable organizations.

“Most often in these countries, aid is donated by high-income countries or companies. But it doesn’t much support the people there,” Yen says. “We are not a charity. We’re building partnerships in those countries to make them more sustainable.”

Yen adds that PhagePro is a for-profit company with a social mission; profit doesn’t completely drive decisions. “Simply throwing money at the problem or constantly donating supplies or drugs won’t work,” she says. “We have to build strong in-country partnerships and integrate situational analysis of vulnerable communities at the start of research and development. That way, the product will work and be accepted by the community. By leveraging our business relationships, ultimately we invest in, not donate to, our in-country partners to create new infrastructure for antimicrobials in their own countries.”

We have to build strong in-country partnerships and integrate situational analysis of vulnerable communities at the start of research and development.

Bacteriophages, also called phages, are significant, she says, because they work immediately to kill cholera bacteria in the gut and stop the disease from developing. They are also effective against drug-resistant forms of cholera bacteria, which have developed in many parts of the world in response to the widespread use of antibiotics. And unlike many antibiotics, phages don’t disturb the good bacteria in the intestinal tract, which is essential for good nutrition and health and for guarding the body against other pathogens.

While phages were discovered 100 years ago and antibiotics not until the 1940s, antibiotic use took over in Western Europe and the US because “it kills bacteria indiscriminately, and we decided to go with the easy route,” Yen says. And yet, in some places, as in Eastern Europe—in the country of Georgia, for example—phage therapy continues.

While the past decade has brought more prudent use of antibiotics (“it’s part of the policy discussion and is more in public awareness”), pressure from big pharma and sometimes the patients themselves make it unlikely that phages will replace antibiotics, Yen says. Long term, however, she expects phages will become a powerful supplement to antibiotic treatment. Her own company’s work toward this goal, though slowed by the pandemic, is expected to enter clinical trials in 2023. In March, the company received $3 million in funding from the National Institutes of Health to continue its R&D.

Yen earned an SB degree from MIT in biological engineering in 2011. During that time, she says, research internships at the University of Cagliari and teaching opportunities in Rome during IAP through the MISTI-Italy program added to her ability to effectively communicate science. With a passion to study infectious disease, she went on to Tufts to earn a PhD in molecular microbiology in 2016 and a master’s in public health from Boston University in 2019. Yen now lives outside Boston with her partner. Both are passionate about global health and diversity, equity, and inclusion in the life sciences, and lead volunteer organizations focused on inclusion and community—Yen runs a group called Scientists in Solidarity with two friends. For fun, she trains in hopes of running a half marathon and says that during the pandemic she has taken up crocheting to balance her penchant for overwork.

Yen’s work-related milestones, however, are among her proudest. A critical moment in her life, she says, was in 2018 (the same year she was named to MIT Technology Review’s “35 Innovators Under 35” list), when her PhagePro pitch won the startup competition at the MIT Women’s unConference, a gathering held to connect alumnae and to celebrate their successes.

“It was a powerful moment for me. Up until that day, I had gotten so many rejections. I was still growing as a leader, and I had never called myself ‘CEO.’ But at that moment of success on stage, I decided for the first time to call myself the CEO!”

Are you celebrating a milestone anniversary of your MIT graduation like Mimi Yen and the Class of 2011? MIT Tech Reunions will take place as a multiday online event June 4–6, featuring special online events for reunion-year classes.

Not celebrating a reunion this year? The entire MIT community can learn from faculty during Technology Day, watch the online Tech Night at Pops, and explore sessions that highlight the MIT campus, programs, and departments. Learn more about how you can participate in Tech Reunions.

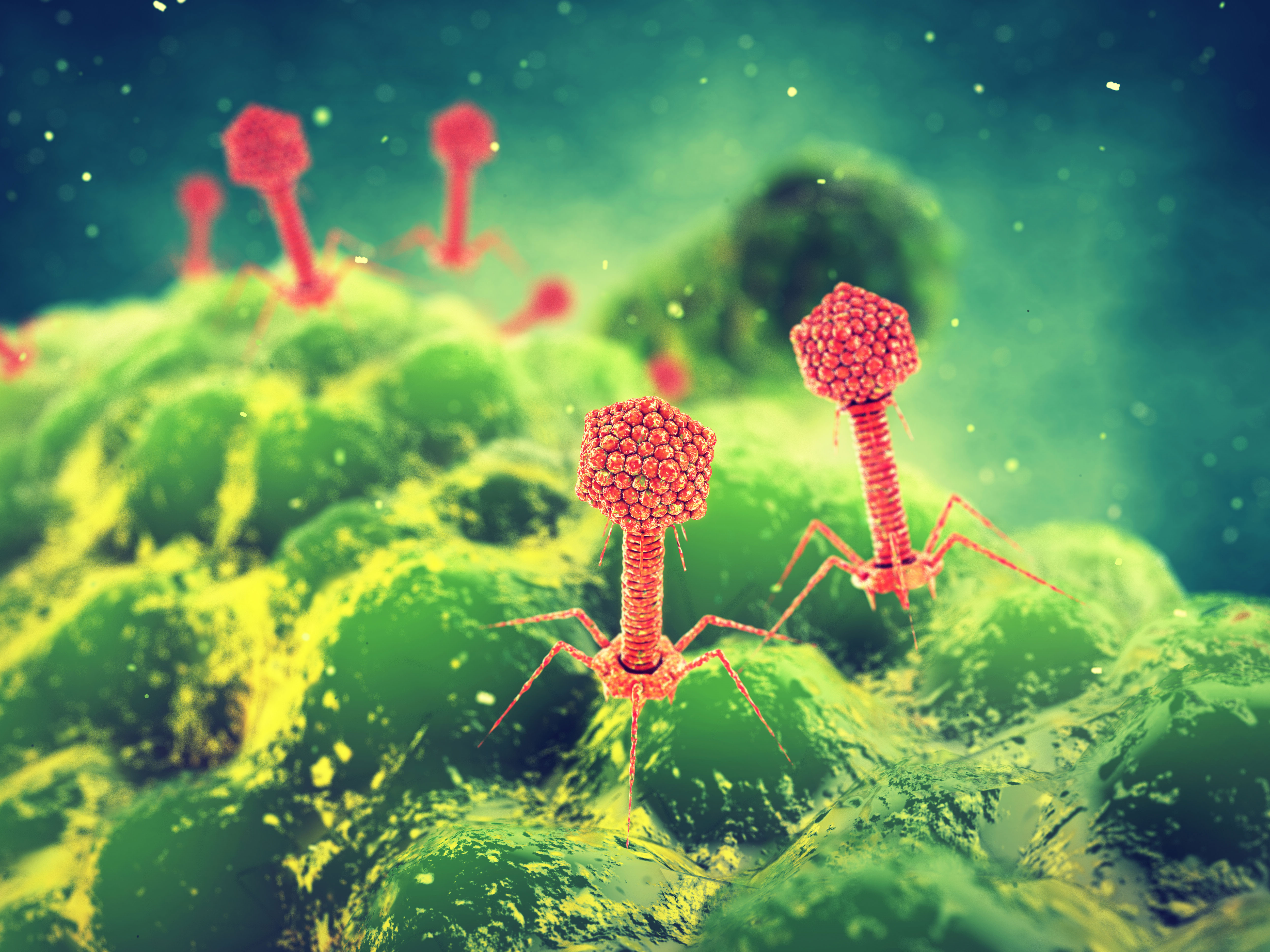

Illustration (top) of phages attacking bacteria: nobeastsofierce/Shutterstock.