Wielding Science and Tech, She Creates Art That Imitates Life

-

-

Slice of MIT

Filed Under

On Saturday, September 26, Ani Liu SM ’17 will speak at the MIT Virtual Alumni Leadership Conference about her experience in a creative sprint organized by the MIT Media Lab and Google Arts & Culture. Reserve your spot at alc.mit.edu to attend her session and others throughout the free, multiday online conference, which begins today.

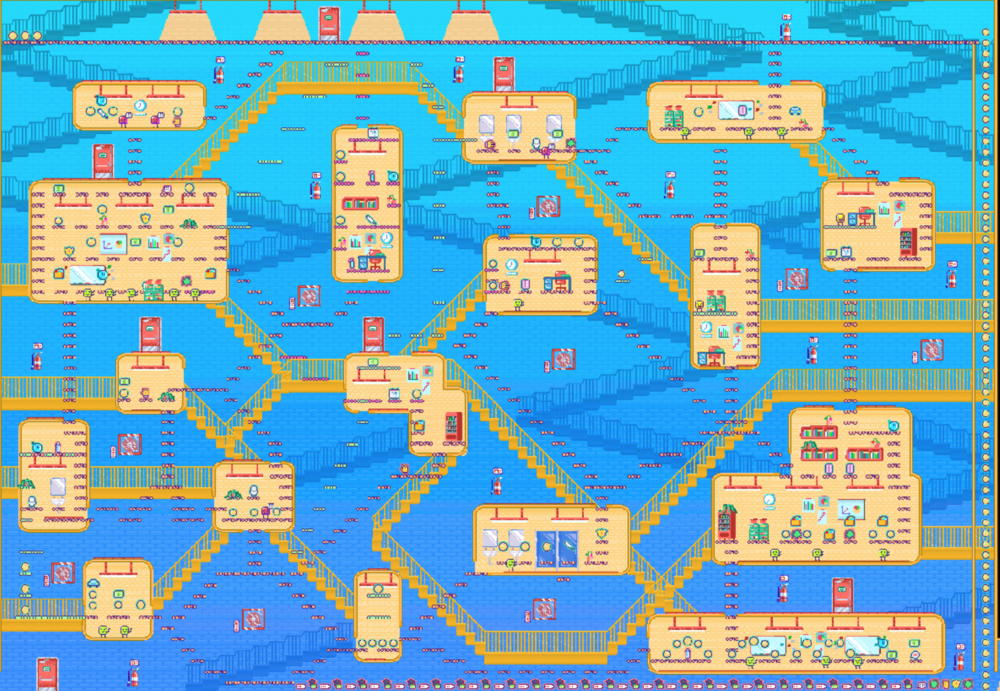

Let’s say, at the start of the video game, you opt to play as a circle.

Your character’s shape is important, but it’s not immediately clear why. Artist Ani Liu SM ’17 has designed it that way. You do know that your objective is to ascend the professional ladder from lowly intern to exalted CEO. But, as in life, some have it easier than others. You’ll see when you play.

Liu has imbued the video game—a work in progress called Shapes and Ladders: Battles of Bias and Bureaucracy—with dark truths about the kinds of systemic challenges faced by marginalized people, such as those who are Black, women, immigrants, gay, trans, or differently abled. In the game world, circles and triangles are much more likely to encounter sexual assault in the workplace. Circles earn 80 cents for each dollar earned by squares. And other insidious disadvantages lurk, depending on your shape’s corresponding identity: having to work “a second shift” of childcare or housework, lacking maternity leave, or facing a higher mortality risk in encounters with police. “The shapes are preloaded with statistics taken from real life,” explains Liu, who started the project, which she describes as a “first-person empathy narrative,” as part of her 2019–21 Arts Fellowship at Princeton University.

An award-winning interdisciplinary artist based in her hometown of New York City, Liu has exhibited at Ars Electronica, the Queens Museum biennial, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, MIT Museum, and many other venues. Her work will appear at the next Venice Architecture Biennale (curated by the dean of MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning, Hashim Sarkis) in May 2021. “I often use the tools of science and technology to create aesthetic experiences,” says Liu—experiences that sometimes question the ways society fails to be humane.

Inequality has recently come to the fore because of Covid-19. “One of the things about the pandemic that struck an emotional nerve with me,” says Liu, “is how it exposed the systemic racism in our society.” In real life, Covid-19 infection and mortality rates skew based on race. So Liu’s video game characters experience the same biases.

Creations of Memory, Power

Before the pandemic, Liu’s pieces were predominantly physical, even sensuous. As a graduate student in the Design Fiction research group at the MIT Media Lab, she speculated on the yearnings of future space travelers on one-way journeys. For them, she created time-capsules of Earthly scents like the ocean, dirt, and a the smell of a loved one. Another piece, Kisses from the Future, showed how a full-lipped kiss embedded in a petri dish would reveal, with time, the cosmic, alien beauty of multiplying microbes.

In her work, Liu seeks to constantly bridge the intellectual with the visceral and the emotional. The potent combination can shift viewers’ perceptions of what is real—and what is possible.

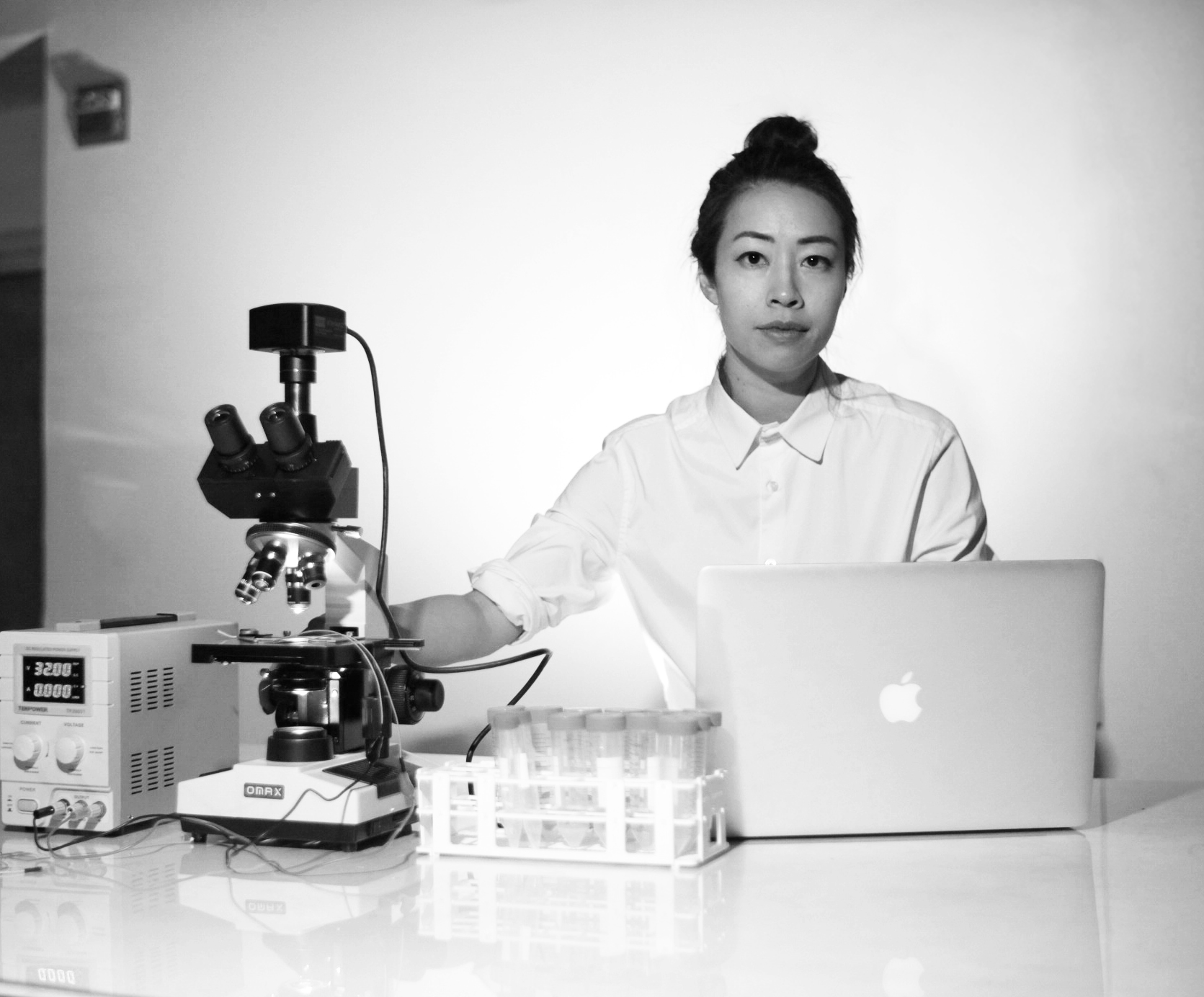

One interactive example—her MIT thesis, Mind-Controlled Spermatozoa—reflects what Liu describes as the absurdity with which men have historically exercised rights over women’s bodies and reproductive health. The piece features live sperm swimming in an electric field: Change the direction of the electric field and, through a quirk of their biology, the sperm follow suit. By connecting the mechanism that controls the electric field to electrodes worn on a user’s scalp, Liu makes it possible for that person’s thoughts to control the sperm. What happens when a woman dons the electrodes to take control of something so symbolically male? “I found it strangely empowering,” said Liu in an interview with PC Mag.

Prior to her time at MIT, Liu earned degrees in arts and architecture. Yet Mind-Controlled Spermatozoa, like many of her works, spans the realms of computer science, neuroscience, biology, chemistry, and engineering. “When I was young, I was often told that girls are not good at certain things, including science and engineering. It wasn’t until I was making art with these tools that I was like, ‘Actually, I can build a circuit!’ Or ‘Actually, I can program this!’” says Liu. “Each technical skill I gain, it’s from having an artistic vision, and really needing to learn a particular technique. That helped me to overcome the anxiety of ‘Can I do this?’”

Now she is teaching others to do the same. Liu has designed a fall course for Princeton, Futures for All: Reimagining Social Equality Through Art & Technology. In addition to providing technical skills in areas like augmented reality and 3D modeling, she’ll be fueling creativity with context: discussing structures that contribute to social inequality, and challenging her students to imagine how the world might be different.

What Ideas Are Made Of

Liu’s ideas have a dash of serendipity in them. “MIT was just such a wonderful place to collide into all kinds of different people who are experts in such varied things,” says Liu. “Sometimes, when I learn about something, I think there’s such a powerful conceptual underpinning that I have to pursue it.”

And bolstering that serendipity is a system: “I’m kind of nerdy, so I have a little database that I built, in which, whenever I read an interesting paper, or poetry, or fiction—if there’s a phrase that I like, I catalog it,” says Liu. “I tag them by an emotion, like longing, or I tag them by conceptual theme, like neuroscience or cognition.”

Her own experiences, such as becoming a parent, also guide her to certain projects. “When you’re pregnant, people immediately want to know, before anything else, the gender. And then when you get gifts, they’re all either pink or blue, and it’s very—I don’t know—binary. And of course, we know gender is not binary.”

Now, Liu is using a machine learning model to process data from Target, Walmart, and Amazon about the features of toys tagged as gendered or gender-neutral and to generate descriptions of hypothetical new toys marketed for boys (example: the “Aqua Shark Adventure Playset”) and girls (the “I Only Sew Designed By You Fashion Studio”). “It is kind of uncanny the kinds of things that pop out,” says Liu.

We also assign gender to technologies, she notes. “Especially technology that we want to be obedient is always female.” These include the voices of Amazon’s Alexa, Apple’s Siri, and Microsoft’s Cortana. So, Liu is developing her own gendered chatbot, prompting those who interact with it to “examine their own implicit biases.” For example, the chatbot, in either a female or male voice, might ask, How much money do you think I make? Or When you envision a doctor, what do you think a doctor looks like?

Ultimately, Liu hopes those who experience her art come away with their own reflections. “I really don’t want to preach from a soapbox,” says Liu. “I like having the pieces be somewhat open-ended or interactive. Because I think there are many ways that these encounters can go, which reflect the complexities of life.”

For Liu, creating art transports her. “There does feel, for me, moments in which something else takes over my body or the piece. There’s a different energy,” she says. “It’s an addictive feeling.”

All photos courtesy of Ani Liu.