Turning a Seaweed Crisis into an Energy Opportunity

-

-

Slice of MIT

Filed Under

Interested in learning more? Legena Henry SM ’10 will be speaking at the MIT Women's Conference on March 28, 2025, in Boston.

In 2019, Legena Henry SM ’10 and the students in her renewable energy course at the University of the West Indies wondered how to help their island of Barbados become fossil fuel free by 2030. Their first thoughts turned to Brazil—home to the world’s largest fleet of cars that run on sugar-based ethanol. But they discovered the model could not be replicated due to the small volume of sugar cane crops on the island. Even the plentiful distilleries in Barbados that once primarily used sugar cane to make rum now depend on imported molasses.

What happened next was pure serendipity: One of Henry’s undergraduates, Brittney McKenzie, commuted to the lab every day past resort beaches covered in brown mounds of invasive Sargassum seaweed. She noticed tractors and cranes moving the rotting seaweed away and wondered where they took it. Then she had an idea.

“Why don’t we look at sargassum?” she excitedly asked Henry.

Henry and McKenzie set out to test the potential in the lab. After mixing rum distillery wastewater with sargassum, they ran some experiments. “And the thing is, it worked!” says Henry, who has a mechanical engineering master’s from MIT and a PhD from the University of the West Indies (where she is a lecturer).

They discovered the microbes in the mix feed on sugar in the wastewater and digest the seaweed.

Years later, what Henry thought might turn out to be a “nice paper,” has become what she calls a “game changer.”

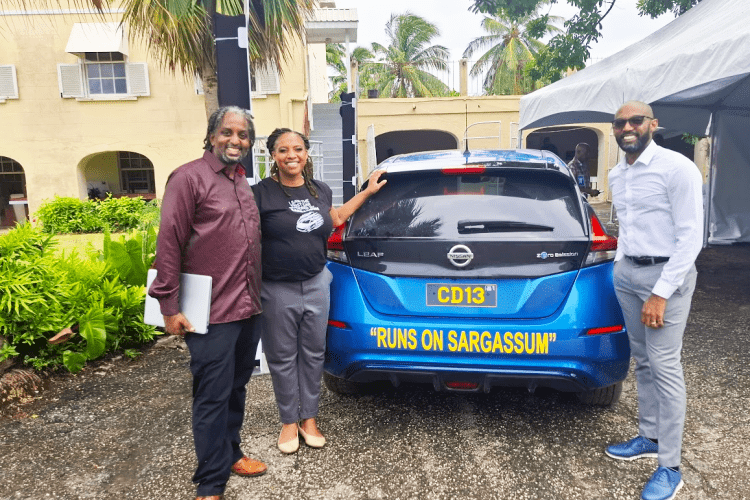

Legena Henry, CEO and cofounder, stands next to a sargassum-powered vehicle during a recent test drive, along with Nigel Henry, cofounder and managing director (left), and Lorenzo Hodges, technical advisor (right).

Sargassum, which has been distributed by ocean currents to become the world’s largest macroalgal bloom, fills over 800 dump trucks on a bad day in Barbados. But thanks to this research, instead of being taken to a landfill, the seaweed can now be converted, with distillery wastewater and Blackbelly sheep manure, into renewable natural gas to fuel cars.

“All the islands in this region of the Caribbean have a sargassum problem and a rum wastewater problem—and ultimately a climate-change problem,” says Henry, in an interview with Nature. “This solution is a win-win-win.”

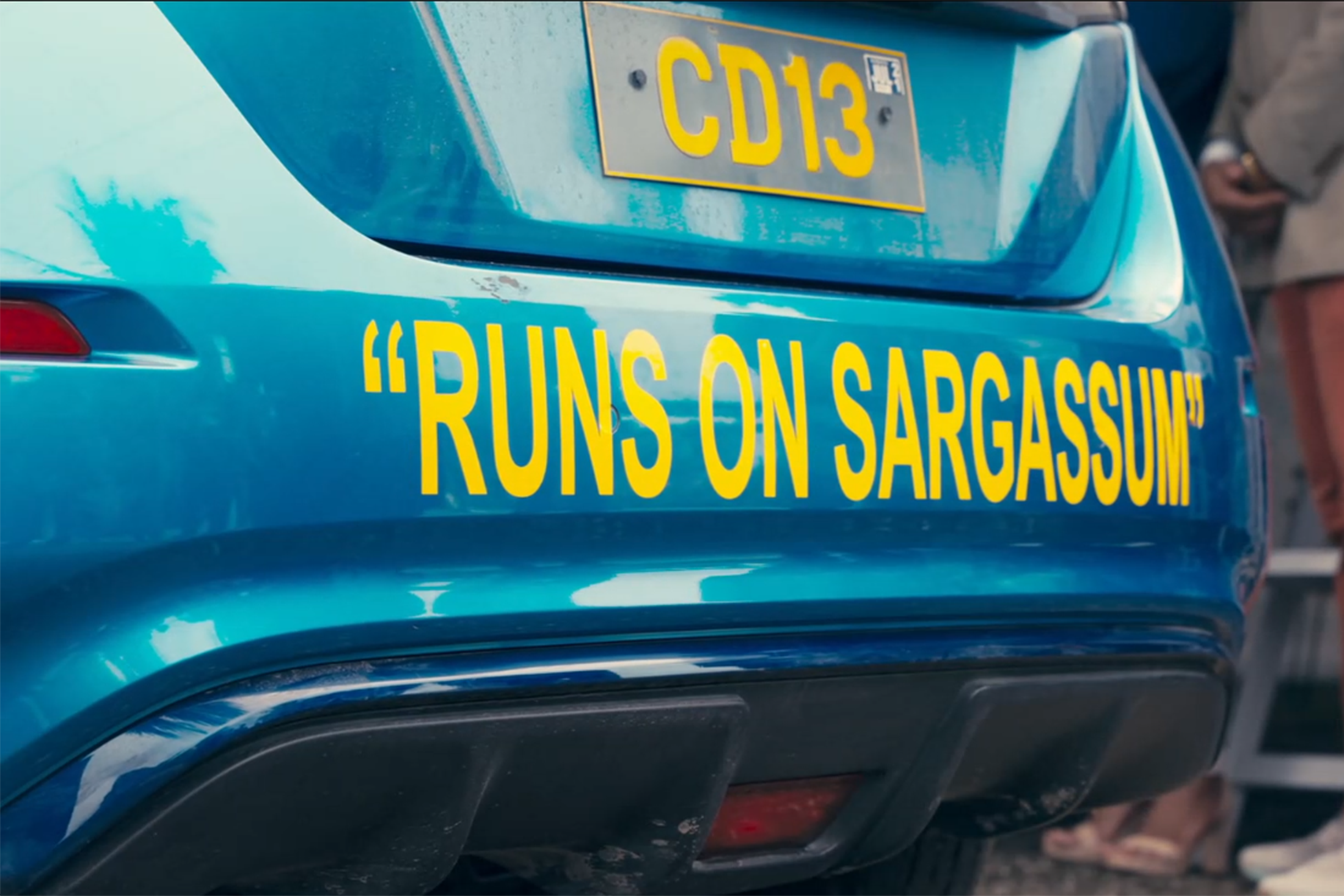

Henry is now the CEO and founder of Rum & Sargassum, a startup established in 2021. The company recently conducted two test drives: one in Barbados in September, featuring a sargassum-powered vehicle, and another in Grenada in October, as part of the Second European Union-Caribbean Global Conference on Sargassum. In both cases, the biofuel operated a portable generator, which in turn charged an electric vehicle.

Henry estimates that if 75 percent of the fossil-fuel-powered vehicles in Barbados ran on the biofuel, it would remove millions of tons of carbon emissions from the atmosphere. It would also halve the cost of vehicle fuel for people in Barbados and potentially help eliminate the island’s dependence on foreign oil.

The startup, working with partners like the Caribbean Centre for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency and Supernova Lab of Future Barbados, is working to scale up production in advance of its first pilot program, scheduled for March 2026.

The project requires collaborating across a wide spectrum of expertise, and Henry says she credits MIT for showing her how the best solutions come from a multidisciplinary approach. It also requires getting support for what some may see as a “small nation” solution, Henry explains. But she is very hopeful.

“Sargassum has now become part of the conversation that will turn the climate crisis around,” she says.

Henry is member of the MIT Educational Council.