Overturning a Century of Misunderstanding Microbes

-

-

Slice of MIT

Filed Under

The fingers of Jared Kehe PhD ’20 cascade across a white electric piano in his Cambridge apartment. Chopin’s Nocturne in E Minor fills the air. “There’s some really profound instances of Chopin pairing together notes you wouldn’t necessarily ever think belong together,” he explains. One particular combination, called a diminished fifth, is discordant in isolation. “Horrible,” summarizes Kehe. But Chopin’s use of tritones in this nocturne are “so beautifully woven into the larger score,” he says, “that they play a very critical musical function.”

Kehe says a similar lesson applies to the microbiome—that the mixing of unexpected microorganisms may well “bring out the best of a microbial community.” It’s the core principle behind Concerto Biosciences, a company that Kehe cofounded in 2020 (along with Cheri Ackerman, a former postdoc at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and Bernardo Cervantes PhD ’20, whom he met and befriended at MIT) and for which he serves as chief scientific officer. “The big vision,” he says, “is to overturn a century of misunderstanding microbes” as dangerous agents of death that must be eradicated with pharmaceutical warfare (read: antibiotics). While some do cause disease, most range from harmless to essential for the health of our bodies and planet.

Kehe considers our skin, which is like a canvas painted with a diverse community of bacteria species. “If I have a healthy protective skin microbiome, I’m much less prone to developing eczema,” he says. “As opposed to someone who has a microbiome that’s imbalanced” with an overabundance of a spherical bacterium called Staphylococcus aureus. Concerto Biosciences’ first big project is to fix this discrepancy and create an eczema therapeutic by delivering a corrective microbial cocktail directly to the skin.

Kehe began developing the kChip, the technology powering the company, while working on his PhD in biological engineering at MIT. He considers himself lucky that he did such “cool, high-potential science” as a graduate student. Today, he says with a smile, he revels in the fact that “it actually works!”

Doing that kind of science in the lab by hand with a pipette, it’s virtually impossible, even with sophisticated robots.

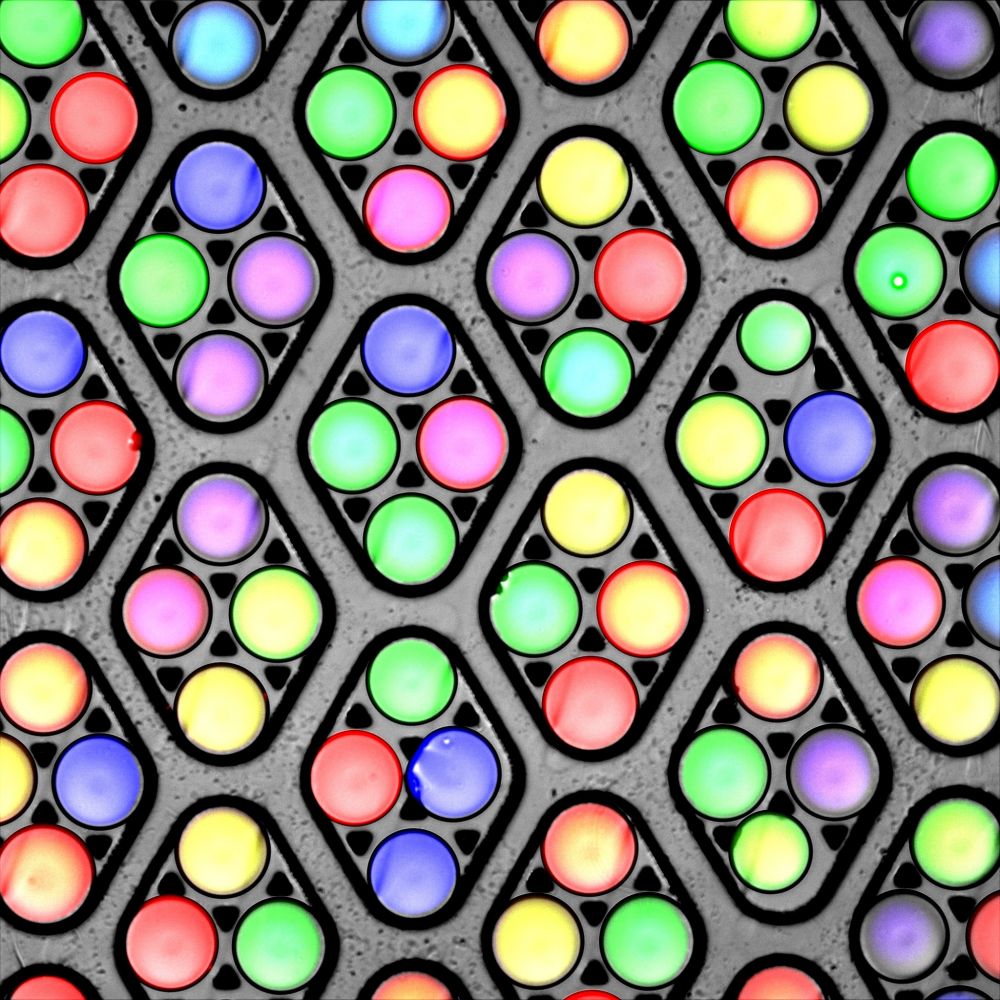

The kChip is a transparent, rubbery piece of material riddled with 100,000 tiny divots. Kehe and his colleagues encapsulate a sea of bacterial cells within a flurry of droplets, each one containing one microbial strain. “Then we take thousands of those droplets,” explains Kehe, “and we flow them over this kChip and they randomly group themselves” into those divots, resulting in “every single possible combination of droplets.” Staphylococcus aureus is already present in each droplet as well, so the researchers then look to see how well the different bacterial combinations interact to punch down (“pacify, not kill”) the eczema-causing bacteria.

Without this technology, the sheer number of different combinations that would need to be tested becomes overwhelming quickly. “Doing that kind of science in the lab by hand with a pipette,” admits Kehe, “it’s virtually impossible, even with sophisticated robots.” The kChip is a solution to that problem. And once the winning combination of three or four microbes is identified, Concerto Biosciences intends to create a spray or ointment that can be applied topically to treat someone’s eczema. At the moment, they’re in the process of developing the product and preparing to conduct in-human studies.

In the coming months, Kehe says the company will expand its scope dramatically, applying microbiome research and the kChip technology to much more than skin. They want to enhance agriculture by introducing combinations of microbes to the soil or plants “to improve crop yields or pest management” without the use of pesticides. They also hope to work on the vaginal microbiome to treat conditions like yeast infection and bacterial vaginosis.

And at some point, Kehe says, it’s his dream to bring the metaphor full circle and unite two of his passions by outfitting the lobby of Concerto Biosciences with “a beautiful grand piano.”