Life in Metal: the Making of a Sculptor

-

-

Slice of MIT

Filed Under

Richard Edelman ’70 has been a clean-cut Midwestern boy, a long-haired antiwar radical, a published poet and founder of an underground press, a brisk and expeditious businessman, and now, at age 72, a celebrated sculptor whose artwork stands as tall as 25 feet in botanical gardens, universities, and synagogues around the world.

His artwork, like his life path, defies a pat description. From hand-size celebrations of found objects (wrenches, drill bits, scrap steel) posed like dancers in motion, to life-size classical sculptures of the human form, to oversize modernist stabiles cast in foundries and assembled outdoors using ladders and scissor lifts, Edelman’s work has found the kind of public exhibition and appreciation most artists hope for. And he only tried his hand at the craft for the first time at age 58.

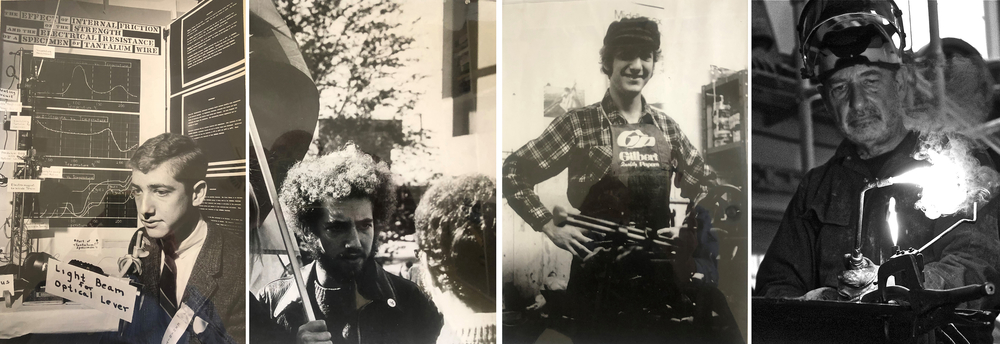

What does unite the Milwaukee-based sculptor’s work—and his many lives prior to sculpting—is his medium: metal. The son of a scrap-metal businessman, Edelman grew up tinkering. At age 17, he won top honors in an international science fair with a project so entertainingly nerdy he keeps a framed black-and-white photo of it in his home office. In the snapshot, his well-coiffed teenaged self sits in front of a poster board proclaiming “The Effect of Internal Friction on the Strength and Electrical Resistance of a Specimen of Tantalum Wire.”

It was that curious scientific mind that brought him—raised in Iowa and Wisconsin, never having seen the Atlantic Ocean—to MIT in 1966. The memories of that time are still bright: arriving at the campus gymnasium, where the freshman footlockers (sent weeks ahead), were laid out alphabetically; taking “anything and everything” MIT had to offer academically, from psychology to philosophy, poetry to engineering. But as the Vietnam War’s reverberations reached Cambridge, Massachusetts, so did a call to radicalism. “I went into school one way and had an experience that led me another way,” Edelman says. The man who emerged from MIT—after engaging in citywide protests and sit-ins, becoming a founding member of the Rosa Luxemburg Students for a Democratic Society, and joining the group that stormed MIT president Howard Johnson’s office in January 1970—was no longer the boy who’d arrived four years earlier with the neatly packed footlocker.

When the war ended, so too did Edelman’s enchantment with radicalism. After working odd jobs, publishing two books of his own poetry while serving as an assistant to poet Denise Levertov, and founding and operating the Hovey Street Press in Cambridge, he returned to the Midwest in the late 1970s and began a career in the steel industry as a metal trader. He started what became a successful 50-employee business, the Essex Trading Company, and sold his interest in it in 2010. While it was different from the scrap-metal business around which he’d grown up—no big machines shredding and “cubing up metal like Goldfinger,” as he describes it—it kept him in the world of that deeply familiar material. It was through his company that he met the welders, blacksmiths, and foundry workers that he would later turn to as providers of raw materials for his art and as trusted collaborators and executors of his own sculptural designs.

As he transitioned out of the business world, Edelman began taking night classes in welding and sculpture, which he had never formally explored despite his lifelong kinship with the basic raw materials—pig iron, stainless steel, bronze, and copper. What began with a love of found form evolved into highly designed, hand-drawn, and hand-modeled pieces, scaled up and either cast or assembled mathematically from circles, triangles, and repeating shapes plasma-cut on industry machines.

By word of mouth, Edelman has attracted commissions in his city and beyond. One recent piece, an expressive depiction of an ibex on a horse with an ostrich titled Cyberglyph, is installed at Ben Gurion University in Israel. His works on public view in Milwaukee today include 25-foot painted steel dancers for Pocket Park and a 15-foot sundial fashioned from railroad rails at the Boerner Botanical Gardens.

And on the Jewish High Holy Days, the baal tekiyah, Hebrew for “shofar blower,” sounds a ram's horn trumpet into a 7-foot-tall, 12-foot-long hollow stainless steel structure created by Edelman for one of Milwaukee’s Jewish temples. Sculpted from equilateral triangles of stainless steel, it’s a modernist’s take on the twists and curves of the ancient instrument's shape. Like the horn itself, the artwork is acoustically tuned to amplify sound.

When he designed the shofar, Edelman knew it would resonate acoustically, but precisely what it would sound like, he wasn’t sure. “It was half science and half art,” he explains. He’d try it one way, have the musician blow the shofar into it, and then make adjustments.

“You have to have a feeling for it,” Edelman says of his process, but that feeling comes from a latticework of experiences he’s pieced together over a lifetime. “You get to know certain materials,” as he puts it—their properties, what they will and won’t do. As for what happens artistically… He pauses to laugh, before answering, “Well, that’s the challenge of it all, isn’t it?”

Photo (top): Jacob's Ladder, Edelman's first fully rendered human figure, cast eight feet tall in bronze (2013). Sculpture and studio photos by Ryan Hainey/RH Photography. All other photos courtesy of Richard Edelman.

Are you celebrating the anniversary of your MIT graduation like Richard Edelman and his fellow members of the Class of 1970?

MIT Virtual Tech Reunions, on Saturday, May 30, will feature special online events for reunion-year classes, plus fun and insightful programming for all MIT alumni. Learn more about attending Virtual Tech Reunions.