Grad Life: From Neurons to Language

-

-

Slice of MIT

Filed Under

Recommended

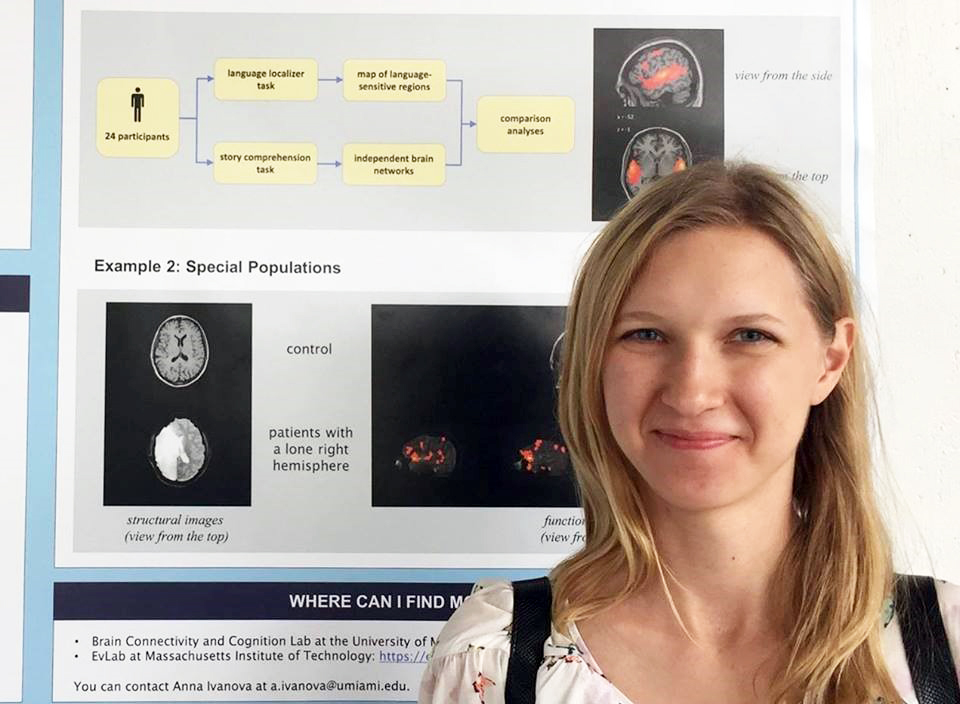

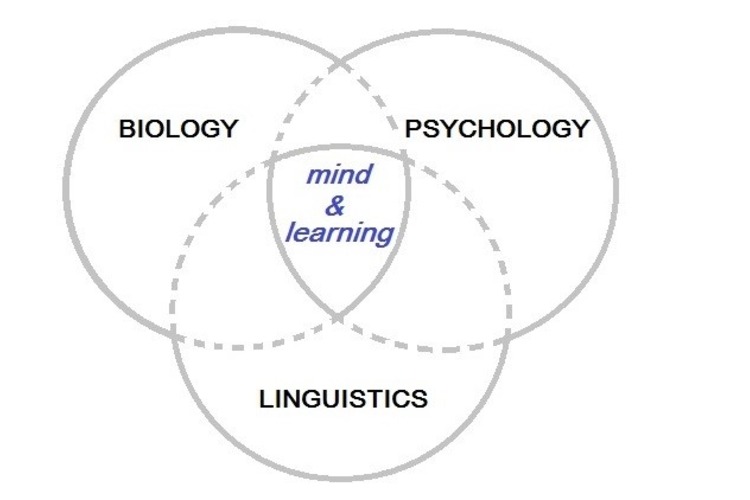

When I was waitlisted for MIT undergraduate admissions, I put together a statement that would serve as an addendum to my application. It included a Venn diagram that depicted my scientific interests at the time. Not a single person from the waitlist was accepted that year, but little did I know that four years later I would find myself here at MIT, doing research that is best described by the picture I made as an 18-year-old.

Drawing by 18-year-old Anna Ivanova.

Let me try to recall the academic background of my classmates. Engineering, biology, neuroscience, psychology, computer science, linguistics… Diverse, isn’t it? Some people remain within the bounds of their respective field for most of their graduate careers. Some, like me, are at the intersection.

I care deeply about both the human brain and the human mind. There are days when I rush from a lecture on neural mechanisms of memory to a talk about Japanese phonetics. I get upset that I no longer keep up with recent discoveries in biology and, at the same time, worry that my knowledge of linguistics is superficial at best. As I try to define the bounds of my research area, they seem to expand to infinity.

Scalar implicature? Ah, right, it’s a language feature that allows us to deduce that the phrase “some people came to class” likely means that not everybody was there.

Gamma power? I think it’s the frequency of brain signals that reflects underlying neural activity.

Fusiform gyrus? Syntactic parsers? Monte Carlo simulations?..

This flurry of vaguely familiar terms is overwhelming at times. Standing at the intersection, I can peek within each discipline, only to realize the vast volume of knowledge that is still beyond my reach. I second-guess most of my decisions when it comes to research, since the field is so new that there are few, if any, gold standards. In an attempt to weave different threads of science together, I often feel tied up in between.

However, during moments of insecurity, I remind myself that this diversity of ideas is exactly what I wanted. I love combining knowledge from different fields. Merging disciplines opens up a whole new space of opportunity, an entire range of questions to explore. Instead of going through the same protocol every day, I am learning a broad set of skills that might be useful for my work (last semester they included MRI data collection, building probabilistic models, and designing a webpage using JavaScript). I can bring together decades of linguistic research and the power of modern neuroimaging to learn more about both brain and language. To be honest, I am still figuring out what exactly I need to know in order to be a neurolinguist. Nevertheless, I am proud to call myself one.

Even when I’m not working on a research project, the interdisciplinary atmosphere never quite goes away. Soon after my classmates and I arrived at MIT, we recognized the diversity of our collective knowledge – so we decided to start sharing what we knew. Every Friday, one of us gives an informal lecture on a topic of our choice. So far we’ve had talks on topics as diverse as microscopy, neural networks, and child development. Most of us will never use this knowledge in our professional life, yet we appreciate this opportunity to broaden our intellectual horizons.

Interdisciplinary research is tough. It includes a constant lack of time, a never-ending avalanche of new terminology to learn, and, of course, an incessant worry that I don’t know enough about any of the fields I’m interested in. Still, the challenge is worth it. Rushing from lecture to lecture, swaying slightly under the load of new information, reaching out to many disciplines at a time…I have never felt more alive.

Grad Life blog posts offer insights from current MIT graduate students on Slice of MIT.

This post originally appeared on the MIT Graduate Admissions student blogs.