Grad Life: MIT Is Less an Ivory Tower, More a Market Square

-

-

slice.mit.edu

Filed Under

Recommended

Just three letters— ‘M-I-T’—can carry a lot of weight.

And, at first, taking those letters on myself—on my sweatshirt, in my job description, in my daily conversations—brought a lot of weighty expectations.

As I prepared to start my PhD in biological engineering in fall 2014, I can recall two distinct feelings: thankfulness for the privilege and anxiety for the task at hand.

The thankfulness is not hard to understand, especially considering how sure I was that I wasn’t MIT material. I was so grateful for the chance to come to MIT, to train in the field of chemical biology, and join the ranks of scientists focused on cancer research.

And, as that gratitude sunk in, the anxiety snuck in right on its heels.

You see, when I answered the question, “So, what will you study at MIT?” with “cancer,” the response was almost always: “I hope you find a cure.”

Now, I know that revolutionary treatments in any disease take a decade or more to develop, and that my graduate work, though related to cancer treatments, would not be a drug discovery project.

Nonetheless, I felt a deep responsibility to actually make some real, albeit small, impact on cancer. To make an impact on a disease that’s threatening my friends and my family. The disease that may be threatening yours.

And the anxiety came from not knowing how to do that. How could my graduate work make an impact on this emperor of all maladies? How could five-and-a-half years (on average) of my tinkering in the lab make a difference? How could my individual contributions made from some tucked away bench top even make a dent?

But, in retrospect, this particular anxiety was underpinned by a belief that at MIT I would be on my own—tucked away in some forgotten corner of campus. I imagined that the privilege of studying at MIT meant I’d be locked away in an ivory tower, secluded from other scientists and struggling to make headway. But it has been very good news that MIT is neither isolating nor withdrawn.

In fact, MIT is less an ivory tower and more a market square. It’s a bustling place of business and innovation, where the best goods are on the table and eager minds from far and wide swap stories and trade ideas. It’s a humming engine for innovation right in the thick of Kendall Square and a stone’s throw away from some of the best research hospitals in the US. And for me and my quest to make an impact in breast and prostate cancer, that is making all the difference.

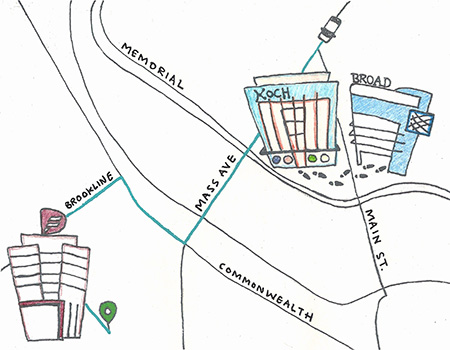

I get to work in the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research on the corner of Vassar and Main. I’m in a lab with synthetic and medicinal chemists, without whom I would certainly never get anywhere fast. I’m down the hall from experts in proteomics, systems biology, and mechanisms of chemotherapy resistance, who are happy to lend reagents and expertise when I’m in a pinch. And I’m just an elevator ride away from a high-throughput science facility, where the experts in automation and assay design have saved me more headaches than I can count.

I get to jaywalk across the street to the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, a group with deep ties to the revolutionary Human Genome Project. Last summer, a seminar there on integrative analysis of genetic regulation immediately reshaped the direction of my research and its applications to patients in the clinic. Last week, I got a new assay up and running in a matter of days, because of the borrowed expertise and equipment of our collaborators in their Chemical Biology and Therapeutics Science Program. With this assay in hand, I have a new tool for studying potential new routes of therapy.

I get to call an Uber and ride over to the Dana Farber Cancer Institute, an institution with an inspirational past that is making a way for a promising future in cancer research. Last summer, when a paper detailing new insights into the initiating events that drive prostate cancer was published by researchers at Dana Farber, we struck up a conversation. I got to give a presentation to the folks I’m always referencing and ask them about the experiments they didn’t publish, yet. As this new collaboration strengthens, we are seeking new ways to work together with the support of the Prostate Cancer Foundation, the stakeholders I care about most.

Now that I am here, I am still thankful for the privilege, but I am also excited by the possibilities. Sharing the responsibility of advancing science in such tangible ways with passionate researchers is what I hope will keep my work far away from some imagined tower and out in the square. And that gets me excited, because, for me, success is not about what papers get published from my little corner of the third floor at 500 Main Street. Success is getting down from the tower and out in the square to push forward so that when someone says “I hope you find a cure,” I can honestly say, “We’re working on it.”

Grad Life blog posts offer insights from current MIT graduate students on Slice of MIT.