Vatican Observatory Researchers Blend Science and Faith

-

-

slice.mit.edu

- 2

Filed Under

Recommended

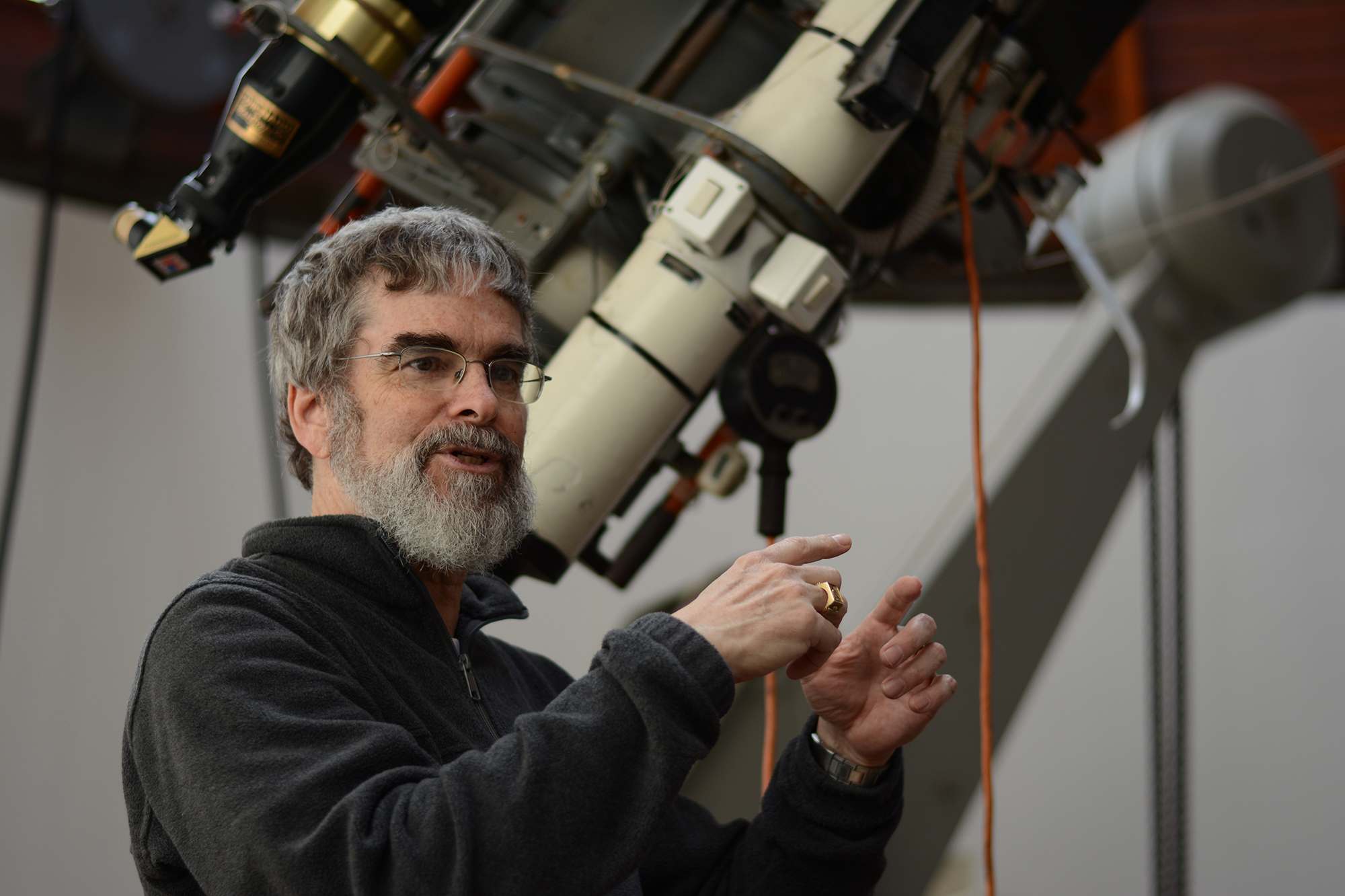

As researchers at the Vatican Observatory—and the only two MIT alumni in Vatican City—Jesuit brothers Guy Consolmagno ’74, SM ’75, and Robert Macke ’96 integrate astronomical research with religion at an institution that dates back more than 400 years.

“It’s a fascinating mixture of worlds,” says Consolmagno, the observatory’s director. “On the surface, faith and science can seem very different, but much like being an MIT student, it reminds people that all the clichés don’t always fit.”

The observatory traces its origins to a group that Pope Gregory XIII commissioned to study the implications of the Gregorian (Western) calendar, which was introduced in 1582. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the papacy and the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) operated separate observatories. Pope Leo XIII merged the operations in 1891 and founded the Vatican Observatory, which today is located in Castel Gandolfo—a scenic town 15 miles south of Rome—and has a satellite location at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

The observatory has 10 full-time researchers plus nine adjunct scholars, and it collaborates with scientists from around the globe, says Macke.

“The observatory exists to show the world that the Catholic church supports science,” says Consolmagno. “Good science is part of the heritage of religious faith. We’re trying to understand how the world works.”

The observatory’s scientists research areas like stellar evolution, galaxy clusters, and quantum gravity. Consolmagno focuses on asteroids and meteorites, and Macke studies meteorites’ physical properties.

Good science is part of the heritage of religious faith. We’re trying to understand how the world works.

Macke, who joined the observatory in 2013, serves as curator of the Vatican’s collection of more than 1,200 meteorites and has studied more than 50 moon rocks obtained from NASA’s Apollo missions.

A lifelong love of astrophysics led Macke to MIT, but it wasn’t until he arrived on campus that he began exploring his religious faith in depth.

“MIT forces you to think about important questions—it’s really where my faith was formed,” he says. “I had friends on campus of all faiths and no faith, and we’d have conversations for hours, and that gave me a reason to explore my own beliefs.”

Macke—who also holds master’s degrees in physics, philosophy, and theology, plus a doctorate in physics from the University of Central Florida—became a member of the Society of Jesus in 2001. He has encountered a few Christians who are surprised to hear about the Vatican’s interest in science but says the larger issue is battling the cultural stereotype that science and faith can’t complement each other.

Br. Robert Macke '96 is curator of the Vatican’s collection of more than 1,200 meteorites.

“I’ve never seen any conflict or problem with being a person of faith and being a scientist,” he says. “In one sense, my faith is why I pursue science. It’s the foundation for my appreciation of the universe.”

Consolmagno was named director of the observatory in 2015. (He celebrated his appointment with Pope Francis over lunch.) A well-known spokesperson for the principle that science and faith can coexist, he has appeared on The Colbert Report and authored 10 books, including Would You Baptize an Extraterrestrial? … and Other Questions from the Astronomers’ In-box at the Vatican Observatory. He is as much a fan of science fiction as he is of real science—he transferred to MIT, after one year at Boston College, thanks in part to its massive SF collection.

“Science is fun—it is part of the reason I was attracted to MIT,” he says. “There is a joy you get when you do science and do it right.”

In 2014, Consolmagno was the first member of a religious order to receive the Carl Sagan Medal, which recognizes outstanding communication by a planetary scientist to the general public. He often finds himself talking about both scientific and ethical issues in astronomy.

“Every time we land a spacecraft on a planet, we’re literally changing the planet,” he says. “And when we place a telescope, we’re altering the ecology of the mountaintop we’re building it on. How much do we have the right to change the planets and mountains that we visit?”

Consolmagno and Macke first met at a scientific conference in 1995. “I actually noticed the brass rat first and the clerical collar second,” Macke says.

Vatican Observatory researchers split their time between Rome and Tucson, and all are expected to fulfill their clerical obligations such as being active in the community and local parishes. And according to Consolmagno, whether they’re pursuing faith or science, the end goal is the same: to be more aware of our place in the universe.

“Faith and science have so many parallels,” he says. “For every answer you uncover, you encounter five more questions. That’s why we’re doing this research—for the joy of discovering the universe. And maybe to show up the guys at Caltech.”

This article originally appeared in the May/June 2016 issue of MIT Technology Review magazine.

Comments

John Stenard

Tue, 05/24/2016 11:07pm

What a great article! A wonderful example of how a person can embrace both a deep faith in Jesus and a deep love for scientific discovery. We need more articles like this. Thanks!

Alan Friot

Mon, 05/23/2016 7:55am

To show real improvement in its recognition of science the Vatican should support my discovery about the earth not being tipped 23.5 degrees. As seen on youtube "Alan's Discovery".