Training Clinicians to Spot Heart Failure in Covid-19 Patients

-

-

Slice of MIT

Filed Under

Recommended

By early February, the health care system in Washington—the first US state to have a confirmed case of Covid-19—was bracing for the spread of the novel coronavirus. When local hospitals began asking for frontline volunteers, 70-year-old cardiologist Florence (Huang) Sheehan ’71 felt obliged, but disappointed, to decline.

“Being elderly was clearly identified as a risk,” explains Sheehan. “But as a physician, I just felt I ought to be doing something more. So when I got an email asking about Covid training, I immediately threw myself into that. I felt so glad that there was something I could do, that only I could do, that I had unique technology to provide help.”

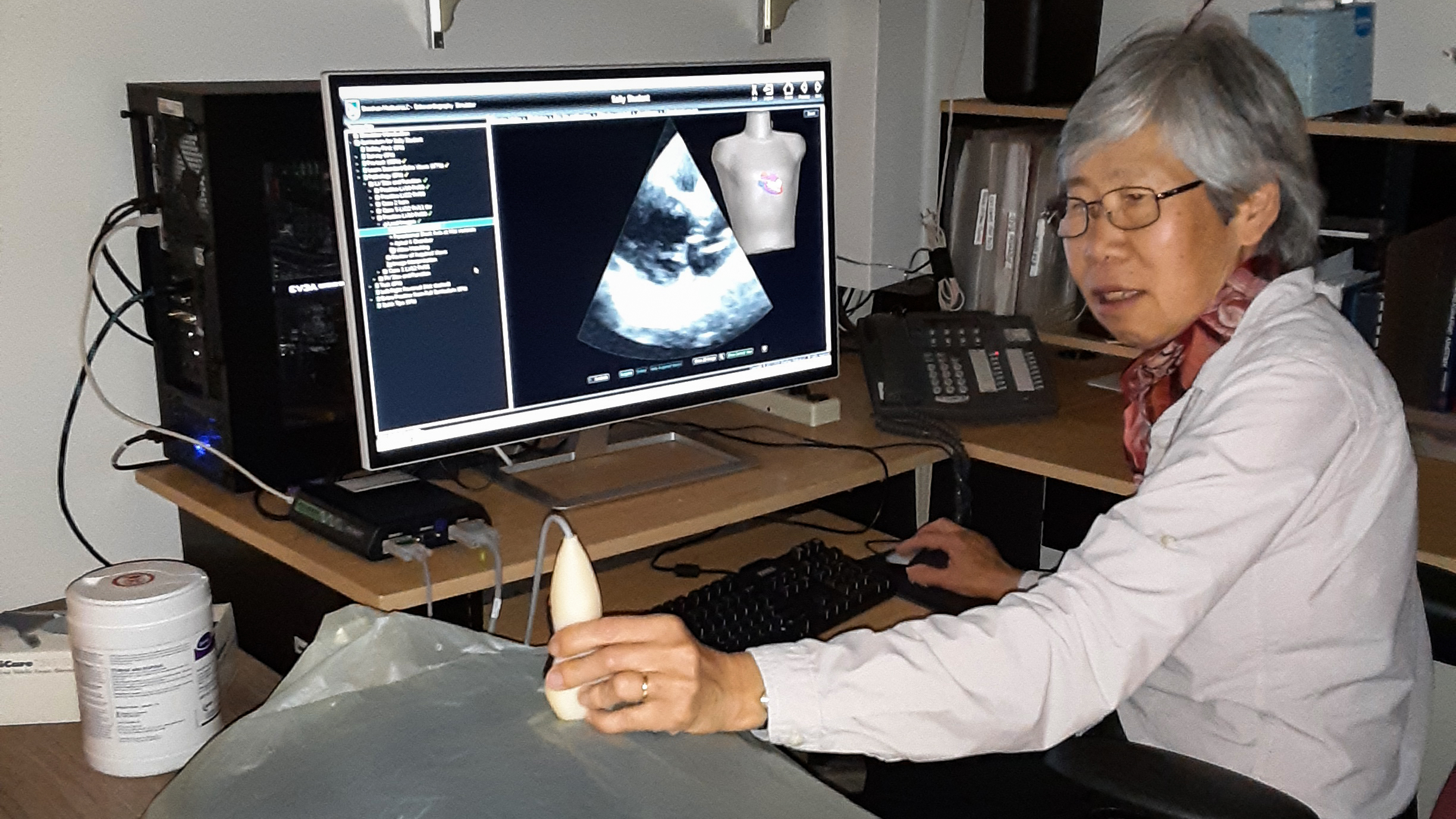

Over the past decade, as a senior investigator at the University of Washington, Sheehan has developed a line of diagnostic medical ultrasound simulators. These devices—consisting of a computer, a mannequin, a mock ultrasound transducer, and a tracking system that tells the computer where the transducer is—are used to train fellows, residents, and medical and pre-med students in performing ultrasound procedures. On March 13, she received an email from the University of Washington Medical Center citing multiple requests from hospitalists for training in bedside cardiac ultrasound so that they could monitor their Covid-19 patients for heart failure, a dangerous complication of the virus.

“Patients were developing heart failure even when they looked like they were recovering from their lung infection,” Sheehan explains.

Within a week, she reworked her standard curriculum and launched coronavirus-specific training in two local hospitals, expanding to a third hospital shortly after. The course is simplified due to the urgent nature of the pandemic; for instance, where the standard course covers seven views of the heart, the Covid curriculum includes only the four that are needed to identify heart failure.

Because properly capturing and interpreting ultrasound images is a very specialized skill, Sheehan has added new features as well. “The Covid-19 curriculum includes a tool that helps with eye training,” says Sheehan. “As you are doing a scan, you see examples of real hearts, comparing the scan you just acquired to hearts with varying degrees of contraction, an indication of heart function. Because they are displayed side by side, and the heartbeats are synchronized, it makes it easier to spot the dysfunction.”

Sheehan says that her training tools are particularly effective because they are the only simulators of their kind to allow real-image display in real time and to provide immediate feedback and evaluation of the user’s success in accurately positioning the transducer and capturing diagnostic-quality images.

Sheehan earned her MD after undergraduate biology studies at MIT. She spent three years at the National Institutes of Health’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, where, in 1977, she became the first woman to hold the position of clinical associate. She completed her training at the University of Washington and joined the faculty in 1982, eventually being promoted to research professor. Sheehan has been working on ultrasound simulators since 2010, and it’s been her most rewarding work, she says. She and her colleagues at the university also built the world’s first vascular and transcranial Doppler simulators (for training clinicians in imaging arteries in the neck, legs, arms, and brain). All of her simulators are available through Sheehan Medical LLC, of which she is the founder and president.

Sheehan traces the blended focus of her career—fusing medicine, engineering, and technology—back to MIT.

“Even though I majored in Course 7, life sciences, I gained a pretty good understanding of what engineering could offer to medicine, so my research has always been on the engineering side of cardiology. From my years at MIT, I have the ability to translate between medicine and engineering. Helping the two parts of the team to understand each other is really quite important.”