Swords Into Plowshares: Reworking a Military Computer in 1972

-

-

slice.mit.edu

Filed Under

Recommended

May 31, 1972 Tech Talk

May 31, 1972 Tech Talk

Guest Blogger: Debbie Levey, CEE Technical Writer

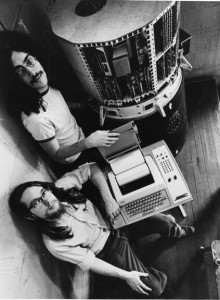

When the Minuteman I missile system became obsolete in the early 1970s, the government sold off the projectiles’ $250,000 computers to schools for a mere $40 shipping fee. In an era of very expensive computers, the EECS Education Research Center (ERC) immediately requested two.

Taking advantage of this windfall for their EECS senior theses, Pat Peterson ’72, SM ’80, ScD ’89 and Andi (Stephen) Tepper ’72 reshaped the computer’s missile guidance function into a general numerical calculator linked to a teletype machine. “We didn’t have a specific long-term plan for what the computer might do,” said Tepper, adding that any machine capable of detailed, complex calculations would be an asset.

Peterson built the hardware interface to connect the teletype machine to the missile computer. “We had a lot of fun,” he recalled, “and we learned a lot about weird computer architectures.” Meanwhile, Tepper wrote an Assembler program for a PDP-7 computer that fed instructions into the missile computer on punched paper tape.

Peterson described the computer’s architecture as “unique, with the cards [circuit boards] surrounding the central core that held the warhead. This computer probably had 8,000 bytes of memory,” enough to direct a missile to its destination. In the days of magnetic core memories, “I think the designers didn’t trust magnetic cores, so they put the memory on a rigid disk an inch thick and about the size of a small dinner plate.” For comparison, his 64 gigabyte cell phone has eight million times more memory.

Making a quiet personal statement with their swords-to-plowshares work, Peterson considered the project “interesting, doable, a little bit anti-war, and pro-having fun.” Tepper concurred, “We would enable this device, whose main job was to cause an immense amount of destruction, to be used for peaceful and even beneficial purposes.”

At the time, the ERC was run by Judah Schwartz in the legendary Building 20. “Everyone knew the building wasn’t permanent, even though it had been there for 30 years. When we needed to run a cable from one room to the next, we just punched a hole in the wall,” said Tepper. “ERC fit in with Bldg. 20 exactly right,” agreed Peterson.

After graduation Peterson joined the MIT Center for Space Research before obtaining his advanced degrees. He now works for BBN on data analytics of call centers, figuring out how well companies take care of their customers, and giving them hints on how to improve. Around 30 years ago Tepper founded Advanced Software Technologies Company to create mainframe computer software mostly in storage management. He is also an adjunct professor of mathematics at Montgomery College in Rockville, Md.

Ariel Weinberg at the MIT Museum provided archival assistance.