Study Reveals Metabolic Master Switch

-

-

slice.mit.edu

- 2

Filed Under

Recommended

Fat cells in human body. Image: shutterstock.

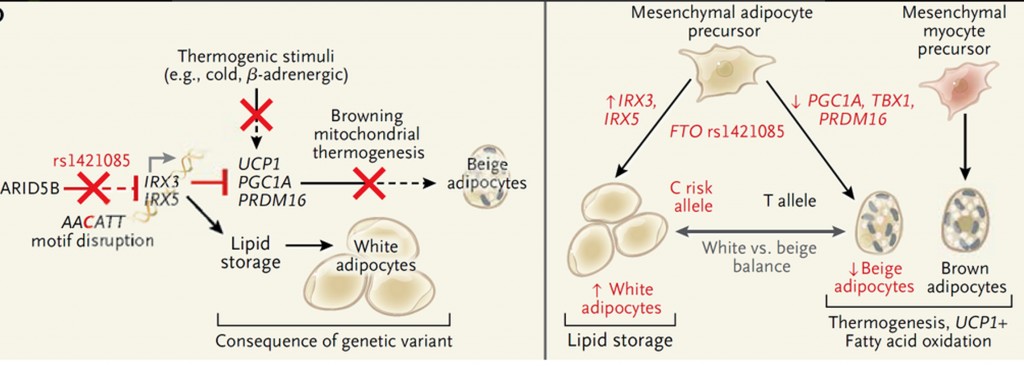

When it comes to understanding obesity, there are several known factors including behavioral, hormonal, and genetic influences. In addition to the most obvious—lack of exercise, poor diet, and eating habits—many have a genetic predisposition. Since 2007, researchers have been able to pinpoint a gene called FTO that is linked to obesity, but until now, not much was understood as to the cause.

How that gene works was revealed in an article published August 19 in the New England Journal of Medicine based on work led by scientists at MIT and Harvard University. This latest work found that the gene directly effects metabolism and the way energy from food is processed. The study showed that a faulty version of the gene actually causes the energy from food to be stored as fat rather than burned.

“Many studies attempted to link the FTO region with brain circuits that control appetite or propensity to exercise,” Melina Claussnitzer, a visiting professor at CSAIL and instructor in medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, told MIT News. “Our results indicate that the obesity-associated region acts primarily in adipocyte progenitor cells in a brain-independent way,”

By studying the genes of both mice and humans, researchers also found that the faulty gene could be turned off, showing promise for a drug in the future that could help treat the defect. “By manipulating this new pathway, we could switch between energy storage and energy dissipation programs at both the cellular and the organismal level, providing new hope for a cure against obesity,” says Manolis Kellis '99, MEng '99, PhD '03, professor of computer science at MIT.

Of course, this isn’t a cure for obesity, because there are many factors at play, but it could be a big help for those with this genetic defect. Also, just because you have the faulty gene, doesn’t guarantee you will be obese. The study did show, however, that people with a faulty gene from both parents, weighed an average of seven pounds more than those without them. “Some were a lot heavier than that,” says Kellis, “and seven pounds can be the difference between a healthy and an unhealthy weight.”

Kellis and study leader Melina Claussnitzer are seeking a patent related to the work. Read more on the MIT News site and the Boston Globe.

Comments

Elaine Taro

Sat, 08/22/2015 2:25pm

Is it possible that this is NOT a faulty gene but a genetic mutation which enabled those persons with this genetic mutation to withstand famine?

Joanna Bryson

Fri, 08/21/2015 7:05pm

Are we sure it's "faulty" to store energy as fat? Sometimes that's useful? Maybe it's a "fault" that younger people dissipate so much energy, wasting food? Maybe it's a "fault" that we feel the need to consume competitively?