Planning Trips to Distant Moons

-

-

Slice of MIT

Filed Under

Recommended

Elizabeth “Zibi” (Pope) Turtle ’89 doesn’t remember a time when she couldn’t name the planets in our solar system. “My grandmother knew all of the myths associated with the constellations,” says Turtle, a native of Wellesley, Massachusetts, who majored in physics at MIT. “My father worked at Hanscom Air Force Base studying auroral phenomena. In my family we were always looking up at the sky.”

Turtle’s eyes—and mind—will be trained even more avidly on the skies for the next two decades while she serves as principal investigator for NASA’s Dragonfly mission to Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. A planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory since 2006, Turtle studies the surfaces of planets and their satellites.

Having taken numerous astrophysics classes at MIT, Turtle says, “I chose to study planets because they are tangible: You can get to them to make measurements.” As researcher and investigator, she has helped NASA do just that in numerous missions, such as Cassini-Huygens, a spacecraft that studied the planet Saturn and its rings and moons (including Titan); Galileo, a spacecraft that studied Jupiter and its moons; and the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, a robotic spacecraft currently studying Earth’s moon. Turtle is also the principal investigator for the imaging system on NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, a spacecraft scheduled to launch as early as 2023 to explore Jupiter’s moon Europa. And with her lead role on the Dragonfly project, which was announced in June 2019, she has become the first female PI of a NASA New Frontiers mission. (NASA’s New Frontiers program was created to tackle high-priority solar system exploration goals that cannot be accomplished within the cost and time constraints of its smaller Discovery missions.)

Titan is a tantalizing venue for studying prebiotic chemistry—the conditions that preceded the emergence of life on Earth. Titan’s surface is etched with a network of rivers, lakes, and even seas of liquid ethane and methane (the main component of natural gas). The ethane and methane evaporate, precipitate, and flow across the surface much the way water does on Earth. This hydrological cycle, along with the presence on Titan’s surface of complex organic compounds and the possibility that these interacted with liquid water in the past, make this moon a compelling analog for Earth before it hosted life.

“I doubt we’ll find water-based life on a moon with a temperature of 94 Kelvin [-290 degrees Fahrenheit],” says Turtle. “The science focus is the chemistry itself, although there is the possibility that chemistry proceeded to biology on Titan. In planetary science, we’ve long learned never to say never.”

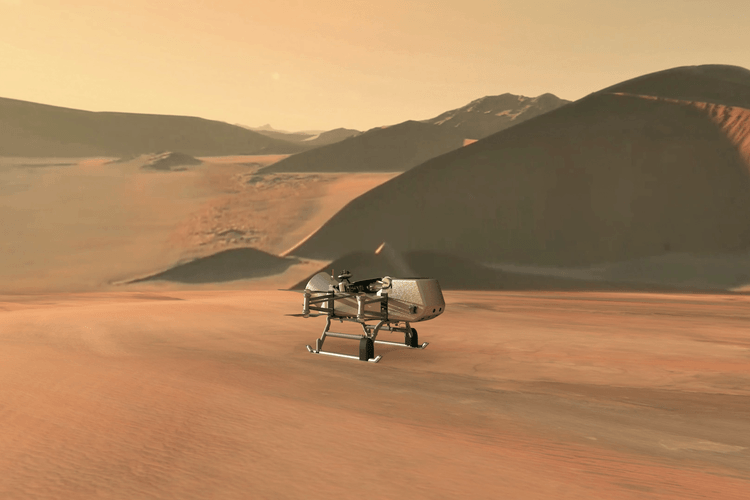

An illustration of Dragonfly approaching a site on Titan. Credits: NASA/JHU-APL

The eight-rotor, roughly 600-kilogram Dragonfly spacecraft is scheduled for launch in 2026 and for arrival on Titan in 2034 after traveling more than 3 billion miles. During its nearly three-year mission, the craft will fly dozens of “hops” of several miles each through Titan’s dense atmosphere to examine features of the moon’s surface. Soil samples from sites including an impact crater and organic dunes will be analyzed by the vehicle’s mass spectrometer in order to study chemical compounds and interactions similar to those that preceded the emergence of life on Earth. Dragonfly’s instruments will also monitor Titan’s atmosphere and chart subsurface seismic activity.

While Turtle built her scientific foundations at MIT—and later as a PhD student at the University of Arizona—it was through working on missions with NASA that she picked up the managerial skills a principal investigator needs. “Participating in missions that involve hundreds of people and multiple organizations,” she explains, “I’ve learned how important it is to provide each group with the resources and support it needs. I’ve also learned how important it is to maintain communication between those groups, especially in that rich interface between engineering and science that can produce such a wealth of ideas and outcomes.”

The next seven years will be intense for Turtle and her Dragonfly team as they design and build the vehicle and its instrumentation in preparation for the 2026 launch. The following eight years will be equally full as the team refines its scientific program while the Dragonfly craft flies toward Titan. When asked whether dealing with the immense distances of our solar system has altered her sense of time on Earth, she says no. “Then again,” she pauses to reconsider, “I do have dates on my calendar for 2026 and 2034,” she laughs. “I’m not sure how many people can say that.”

Photo (top): Courtesy of Zibi Turtle.