An MIT Engineer’s Rediscovered Role in Lunar Landing History

-

-

Slice of MIT

Filed Under

Recommended

MIT engineer Conrad “Connie” Lau ’42 was a key figure in getting America to the moon, but until very recently, almost no one knew it.

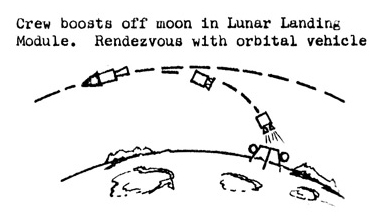

Plans for lunar missions had been in the works for years even before John F. Kennedy committed the nation to “landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth” in May 1961. One of the main questions was just how to do it with the technology available. German rocket engineer and space visionary Wernher von Braun, then in charge of NASA’s rocket program, had always advocated for first building a space station in Earth orbit, then sending a separate spacecraft from there to land on the moon. Others insisted that the most obvious approach was best: simply build a single huge rocket powerful enough to fly straight from Earth’s surface to the moon. The third possibility, called lunar orbit rendezvous, or LOR, would use a modular spacecraft in lunar orbit, including a moon lander to undock from the main ship and then redock after landing so the astronauts could return to Earth.

After much debate, NASA officially adopted LOR as its approach in 1962, and seven years later the Apollo 11 crew flew its three-part modular spacecraft into history. NASA engineer John Houbolt was credited as the chief architect of LOR, the man who had relentlessly pushed it to the agency as the cheapest, safest, and most flexible approach.

But as aerospace historian Robert Godwin recently discovered, the story is not so simple. While it’s true that Houbolt “was the guy who was banging on doors and risked his job to sell [LOR],” Godwin explains that NASA had been pitched the concept long before Houbolt, in a January 1960 presentation authored by Lau.

I see this design for a three-module, lunar orbit rendezvous system. And I noticed the name on the front, and I’ve never heard of this guy before.

At the time, Lau was a senior engineer at famed aircraft manufacturer Chance Vought, where he’d worked since graduating from MIT in 1942 with a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering. He first contributed to development of the famous World War II F4U Corsair fighter, then went on to work on the F7U Cutlass and the F8U Crusader jet for the US Navy, becoming a co-owner of the F8U patent.

By the end of the 1950s, Chance Vought had become one of many aircraft companies jostling for a piece of the new space program pie. One of Lau’s main efforts as chief of advanced projects in the company’s newly established Astronautics Division was called Project MALLAR (for Manned Lunar Landing and Return).

Godwin, who has authored more than 100 books on space history, uncovered information about MALLAR and Lau while working on a book about the International Space Station for NASA. “I was studying up on every conceivable space station that they had actually considered, and I kept coming across the name Chance Vought quite a lot,” he says. He dug deeper until he discovered the MALLAR report, a nearly 200-page document that sets out the modular mission concept and LOR in great detail.

“I started flipping through this thing all excited—wow, this is something I haven’t seen before,” Godwin recalls. “I see this design for a three-module, lunar orbit rendezvous system. And I noticed the name on the front, and I’ve never heard of this guy before. He’s never been mentioned as far as I could tell in any piece of literature that has ever been published on the subject of LOR or Apollo.” As Godwin discovered, however, NASA’s plans for a modular moon landing craft were essentially based on the MALLAR report from Chance Vought and Lau.

Further investigation led Godwin to details of Lau’s background. “I traced his heritage all the way back to early 19th-century China,” Godwin says. Born in 1921 in Trinidad, Lau started his college career there at Queen’s Royal College before transferring to MIT in his junior year. Godwin located his son, Conrad Lau Jr., a software engineer living in Florida.

Conrad Jr. had grown up with a photo of all seven Mercury astronauts hanging on the wall of the family house, signed by all, “Best regards to our good friend ‘Connie’ Lau”—but he hadn’t known of the moon-landing connection. “Godwin reached out to me, indicating that he wanted to do a biography on Dad. And I’m like, oh, that’s kinda cool, but why would you want to do that now, so many years later?”

Godwin filled in Conrad Jr. on what he’d discovered, and when his book Manned Lunar Landing and Return was published this year, Godwin sent him a copy. “I kind of took it with a grain of salt until I read it, and I’m like, holy moly, this is crazy,” the son says. “Dad didn’t get credit for this, and his name’s on it.”

Although he was only 10 years old when his father died, Lau’s son has some vivid early memories of himself and his dad, such as seeing advanced aircraft on a tour of the Chance Vought plant. “It’s really cool stuff, but you don’t really tie any pieces together, what your dad’s role is.” He remembers his father bringing home publicity materials from the Mercury and Gemini projects, thanks to his NASA connections. And more than that: “We had the first seven astronauts at our house at various times for cocktail parties and things. And the one I remember is [John] Glenn.” The strong friendship between Lau and John Glenn seems to have started even before the space program, when Glenn made the first transcontinental supersonic flight in the airplane Lau had designed, an F8U-1P Crusader, in July 1957.

According to his son, Conrad senior had known what he wanted to be from a very early age. “When he was 10 years old, he heard an airplane. He climbs a tree, watches the airplane, comes back down the tree, and tells my grandmother, his mom, ‘I want to learn everything there is about airplanes.’” It turned out that the plane that had enchanted Lau was flown by Charles Lindbergh, whom Lau would eventually work with at Chance Vought. Flight, says his son, “was absolutely his passion.”

It was a passion that, as is now apparent, extended all the way to the moon. Sadly, Lau died young, in 1964 at age 43, before witnessing the realization of his ideas in the Apollo 11 moon landing. But at least his son is seeing his father earn his rightful place in space history.

Mark Wolverton is a 2016–17 MIT Knight Science Journalism Fellow.

Photo (top): Conrad Lau '42, far right, in a photo commemorating the 100th flight of the F8U-3 Vought Aircraft he helped to design. Pilot John Konrad is second from left. Photo courtesy of Conrad Lau Jr.