MIT Bridge Builders Rule!

-

-

slice.mit.edu

Filed Under

Recommended

Guest Blogger: Debbie Levey, CEE Technical Writer

Bridge-building contests have some history at MIT. Mostly recently, MIT students began competing at the National Steel Bridge Competition sponsored by the American Society of Civil Engineers in 2007. Today, they are contenders—they have placed second nationally for the past two years.

As part of a capstone class each spring, Civil and Environmental Engineering Department seniors split into teams to design and build strong, light bridges out of simple materials that could be used to replace washed-out roads or crossings in remote areas. Since 2001, students have created 10-foot-long bridges contrived of wood or recycled materials, laced together with steel cables, just outside the student center—and for the final test, they must bear one ton of concrete blocks.

Earlier still, Civil Engineering professor John Slater ’78 initiated a model bridge building contest for the January IAP session in 1983 to mark the centennial of the Brooklyn Bridge. Three-students teams received a kit of parts, instruction, and lab time for building suspension or cable-stayed bridges to span a river. The IAP description promised “substantial cash prizes to the top three entries with the highest combined scores in strength, deflection, weight, innovation, and aesthetic appeal.” After being examined and discussed, each bridge was then weighed down until it shattered.

“The inevitable explosive bridge failure made for a fun event,” said Slater. These bridge contests, no longer offered, remained a popular IAP event for years.

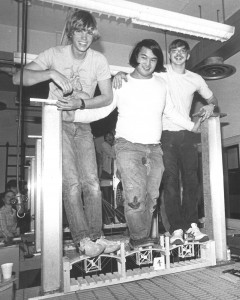

A Tech Talk photo of Lars Rosenblad '85, SM '85; Philip Michael '84, SM '86, PhD '92; and Ling Chow '84 documented their effort. After their 1.06-pound balsa wood design carried all the available weight in the Perini test lab (1,840 pounds), the three students crowded onto the deck to add their cumulative 440 pounds.

Finally the bridge collapsed under 2,280 pounds—and both Rosenblad and Michael report that they still carry small scars from banging into the metal column as they tumbled down with their bridge.

Michael recalled doing research on bridge designs before they started building. “Cable-stayed bridges had really risen to prominence, but given the choice of materials [in the kit], we couldn't figure out a reliable means to tie cables into our bridge decking without the risk of having them pull through. Instead, we adopted the several-millennium-old arc as the basic design element. The one element we adapted from the cable-stayed design was to attach cables to the bridge towers so that any load would simultaneously pull in on the towers to keep the bottom of the arch from spreading outward. Those cables were inelegant but hardly weighed anything and worked extremely well in tension.”

Even though their bridge proved strong and light, low scores in the appearance category pushed them down to a fifth-place finish. Lars acknowledged that “our bridge was judged to be exceedingly ugly.”