Making Steel with Electricity

-

-

MIT News

- 1

Filed Under

Recommended

Steel is one of the most useful materials on the planet. A backbone of modern life, it’s used in skyscrapers, cars, airplanes, bridges, and more. Unfortunately, steelmaking is an extremely dirty process.

The most common way it’s produced involves mining iron ore, reducing it in a blast furnace through the addition of coal, and then using an oxygen furnace to burn off excess carbon and other impurities. That’s why steel production accounts for around 7 perecent to 9 percent of humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions worldwide, making it one of the dirtiest industries on the planet.

Now Boston Metal is seeking to clean up the steelmaking industry using an electrochemical process called molten oxide electrolysis (MOE), which eliminates many steps in steelmaking and releases oxygen as its sole byproduct.

The company, which was founded by MIT Professor Emeritus Donald Sadoway, Professor Antoine Allanore, and James Yurko PhD ’01, is already using MOE to recover high-value metals from mining waste at its Brazilian subsidiary, Boston Metal do Brasil. That work is helping Boston Metal’s team deploy its technology at commercial scale and establish key partnerships with mining operators. It has also built a prototype MOE reactor to produce green steel at its headquarters in Woburn, Massachusetts.

And despite its name, Boston Metal has global ambitions. The company has raised more than $370 million to date from organizations across Europe, Asia, the Americas, and the Middle East, and its leaders expect to scale up rapidly to transform steel production in every corner of the world.

“There’s a worldwide recognition that we need to act rapidly, and that’s going to happen through technology solutions like this that can help us move away from incumbent technologies,” Boston Metal Chief Scientist and former MIT postdoc Guillaume Lambotte says. “More and more, climate change is a part of our lives, so the pressure is on everyone to act fast.”

Since the 1980s, Sadoway had conducted research on the electrochemical process by which aluminum is produced. The focus of the research was to find a replacement for the consumable anode used in that process, which makes carbon dioxide as a by-product. During that work, he began to conceptualize a similar electrochemical process to make iron, the precursor to steel.

But it wasn’t until around 2012 that Sadoway and Allanore, then a postdoc at MIT, discovered an iron-chromium alloy that could serve as a cheap enough anode material to make the process commercially viable and produce oxygen as a byproduct. That's when the pair partnered with James Yurko, a former student, to found Boston Metal.

“All of the fundamental studies and the initial technologies came out of MIT,” Lambotte says. “We spun out of research that was patented at MIT and licensed from MIT’s Technology Licensing Office.”

Lambotte joined the company shortly after Sadoway’s team published a 2013 paper in Nature describing the MOE platform.

“That’s when it went from the lab, with a coffee cup-sized experiment to prove the fundamentals and produce a few grams, to a company that can produce hundreds of kilograms, and soon, tons of metal,” Lambotte says.

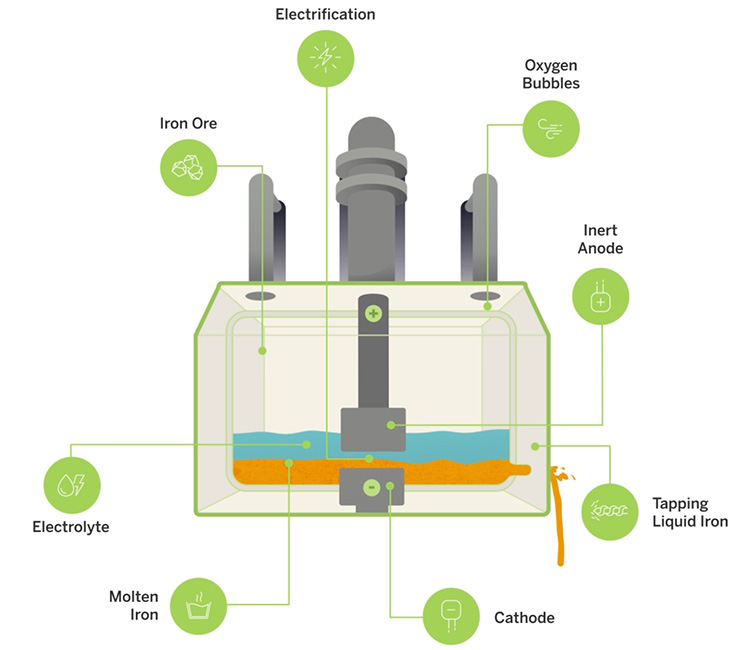

Boston Metal’s molten oxide electrolysis process takes place in modular MOE cells, each the size of a school bus. Iron ore rock is fed into the cell, which contains the cathode (the negative terminal of the MOE cell) and an anode immersed in a liquid electrolyte. The anode is inert, meaning it doesn’t dissolve in the electrolyte or take part in the reaction other than serving as the positive terminal. When electricity runs between the anode and cathode and the cell reaches around 1,600 degrees Celsius, the iron oxide bonds in the ore are split, producing pure liquid metal at the bottom that can be tapped. The byproduct of the reaction is oxygen, and the process doesn’t require water, hazardous chemicals, or precious-metal catalysts.

The production of each cell depends on the size of its current. Lambotte says with about 600,000 amps, each cell could produce up to 10 tons of metal every day. Steelmakers would license Boston Metal’s technology and deploy as many cells as needed to reach their production targets.

Boston Metal is already using MOE to help mining companies recover high-value metals from their mining waste, which usually needs to undergo costly treatment or storage. Lambotte says it could also be used to produce many other kinds of metals down the line, and Boston Metal was recently selected to negotiate grant funding to produce chromium metal—critical for a number of clean energy applications—in West Virginia.

“If you look around the world, a lot of the feedstocks for metal are oxides, and if it’s an oxide, then there’s a chance we can work with that feedstock,” Lambotte says. “There’s a lot of excitement because everyone needs a solution capable of decarbonizing the metal industry, so a lot of people are interested to understand where MOE fits in their own processes.”

Boston Metal’s steel decarbonization technology is currently slated to reach commercial-scale in 2026, though its Brazil plant is already introducing the industry to MOE.

“I think it’s a window for the metal industry to get acquainted with MOE and see how it works,” Lambotte says. “You need people in the industry to grasp this technology. It’s where you form connections and how new technology spreads.”

The Brazilian plant runs on 100 percent renewable energy.

“We can be the beneficiary of this tremendous worldwide push to decarbonize the energy sector,” Lambotte says. “I think our approach goes hand in hand with that. Fully green steel requires green electricity, and I think what you’ll see is deployment of this technology where [clean electricity] is already readily available.”

Boston Metal’s team is excited about MOE’s application across the metals industry but is focused first and foremost on eliminating the gigatons of emissions from steel production.

“Steel produces around 10 percent of global emissions, so that is our north star,” Lambotte says. “Everyone is pledging carbon reductions, emissions reductions, and making net zero goals, so the steel industry is really looking hard for viable technology solutions. People are ready for new approaches.”

This story was originally published by MIT News.

Top photo: iStock

Comments

William Jeffrey

Sat, 08/03/2024 11:53am

Amps vs ergs

"[W]ith about 600,000 amps, each cell could produce up to 10 tons of metal every day."

600,000 amps to produce 10 tons of steel per day? That's a pretty sturdy number. But of course the number of amps isn't what matters. A better number would be the energy - number of ergs or watt-hours - to produce 10 tons per day.

Bill