Making the Invisible Visible

-

-

MIT Technology Review

Filed Under

Recommended

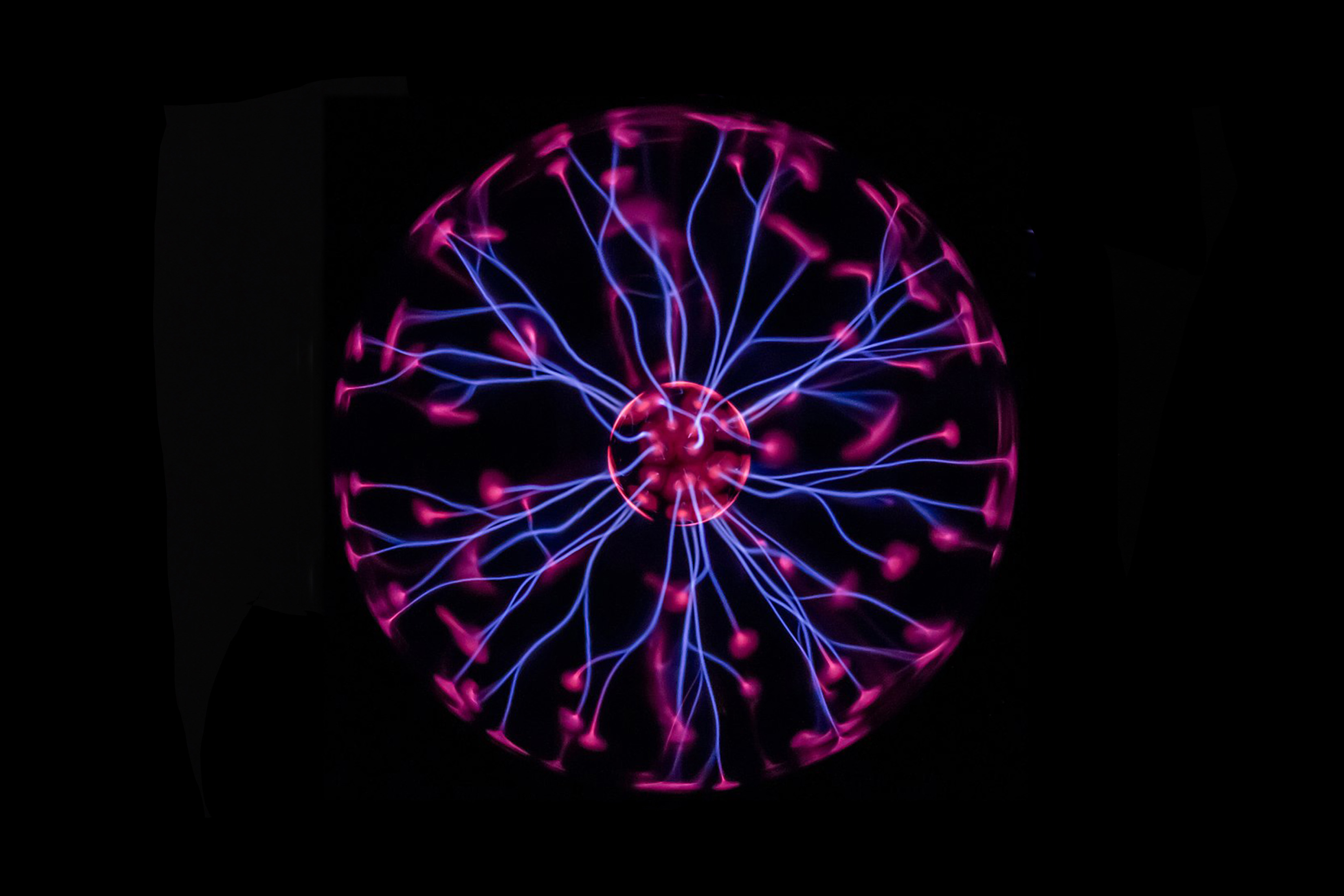

There are probably only a handful of science museums around the world whose collections do not include a plasma globe created by Bill Parker ’74, SM ’93. Coming up with the modern design of that device “was definitely my 15 minutes of fame,” he jokes.

An artist, scientist, and entrepreneur, Parker spent much of his childhood in the basement laboratory of his parents’ Vermont home. While his junior high friends were building go-karts, he built a helium-neon laser. In high school, he shifted his attention to electrified gas plasmas, a medium of unbound electrons and ions that he calls “the most fabulous substance in the world.” He struck a deal with his teachers: if he handed in his homework, he could skip class and experiment with plasma thrusters that might one day propel spacecraft to Mars and beyond. Thanks to those experiments, he was named a finalist in the nationwide Westinghouse (now Regeneron) Science Talent Search.

"You can’t see electricity. And you can’t see gases. But if you combine the two, they become visible."

Parker continued his plasma experiments while earning a bachelor’s in art and design. One day, he turned on the high-voltage power supply to ionize neon gas in a six-foot glass vacuum chamber, not realizing that the vacuum valve was closed. Instead of a stream of ionized exhaust, tendrils of plasma pulsated against the glass. “It was extraordinarily beautiful,” he recalls. “Like a neon lightning storm.”

In his junior year Parker became the youngest fellow at MIT’s Center for Advanced Visual Studies, where he collaborated with its founder, the artist Gyorgy Kepes. “Those were my happiest undergraduate years,” he says. “Making art out of plasma, combining my passions for science and art.” He has since created beguiling plasma displays for hundreds of venues, including the San Francisco Exploratorium, the Boston Museum of Science, and the Universal Orlando Resort. His globes grace thousands of private collections.

After earning a master’s at the Media Lab, Parker channeled his research in electro-optics and holography into commercial augmented-reality devices—rugged near-to-the-eye vision systems that let firefighters “see” through smoke and help military personnel navigate urban battle environments. Creative MicroSystems, the Vermont-based company he cofounded with his wife, Julie Walker ’87, in 2005, counts NASA and multiple branches of the US military among its clients.

“We say we like to give people superpowers,” he says. “You can’t see electricity. And you can’t see gases. But if you combine the two, they become visible.”

This article also appears in the November/December issue of MIT News magazine, published by MIT Technology Review.

Top photo: © User:Colin / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0

Inset photo courtesy of Bill Parker