Everyone has probably seen a conductor, but how much do we really understand their role? According to Sarah Platte SM ’16, not much at all. As director of a performance for an orchestra or choir, the conductor is often revered but sometimes also scrutinized. Some use the term “maestro myth” to question what, if anything, a conductor does to enhance the musical performance.

As a musician, Platte was first introduced to conducting at age 13 but only when she studied the craft in college did she realize how vague and intangible the methods were. Her professor, a well-known conductor, did not use books or visuals and mostly instructed the students to “feel the music,” an experience that drove her to want to better understand the underlying mechanisms from a more scientific perspective.

Platte, who earned a master’s in visual communications and iconic research at FHNW HGK, a school of design in Switzerland, heard about the Media Lab through a friend and applied for the master’s program hoping to studying with Tod Machover, the influential composer (named Musical America’s 2016 Composer of the Year), professor of music and media, and head of the Media Lab's Opera of the Future group. She worked with Machover to design and conduct two studies that resulted in Platte’s thesis titled, The Maestro Myth – Exploring the Impact of Conducting Gestures on the Musician’s Body and the Sounding Result.

“In contrast to previous studies, our research approaches the gestural language of conducting as an intuitively perceivable form of real-time communication rather than a semiotic sign language subject to interpretation and thus open for culture-bound misunderstandings,” says Platte.

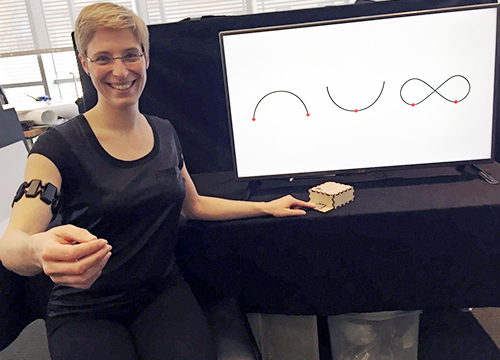

The studies both involved observing the same conductor in the same setting performing three different common types of gestures. “The first study measured timing and pressure of touch-events on a touch-sensor,” says Platte. “Subjects were asked to tap a beat while shown videos of the three different conducting patterns. In the second study, we asked violinists to play single notes following the same videos as in study 1, but here we additionally measured differences in sound-quality.”

Armbands with sensors were used to measure the type of movements and muscle-tensions by the conductor and the sound quality was analyzed to measure the musicians' reactions.

In both studies, they found a consistent and direct correlation between the gestures and muscle-tension of the conductor and the musicians. Their findings showed consistencies in musicians’ reactions to certain types of hand gestures, indicating that how and what a conductor conveys to the musician impacts the performance.

“Our findings do not aim to define any of the investigated types of gestures as being right or wrong,” says Platte. “But it turns out that since every gesture has a unique sounding consequence, certain gesture types are more capable–more economical and effective–of reaching predefined musical/interpretational goals than others. And a higher coherence in the communication between conductor and ensemble improves the overall quality of musical interpretations and performances.”

Platte hopes that understanding the gestural communication language of conducting could help improve performances as well as the relationships between musicians and conductors. She also sees implications beyond the musical world. “An improved and more detailed knowledge about conducting might also influence the overall awareness of and sensitivity to gesturality and the effect of our bodily expressions on others.”

Upon graduating from the Media Lab in May, Platte moved back to Europe to begin her doctoral studies at the new Center for Interdisciplinary Music Research in Freiburg, Germany. She will continue her research on conducting and hopes to focus on the conductor's influence on the human voice.

Comments

Stanton de Riel

Wed, 08/24/2016 9:22am

As a member of a community chorus, I've always been surprised by the time delay between the end of the down-stroke of the baton and the chorus entrance, and subsequently also. Even granting that an entrance-attack needs to not be harsh, no one is producing sound coincident with the "designated instant". Do orchestras do the same thing (which would make them less instantly responsive to tempo changes, as is the chorus), has anyone observed?

David Elaine Alt

Tue, 08/23/2016 6:59pm

From my three seasons studying at the Pierre Monteux School for Conductors and Orchestra Musicians, I can attest that there surely is a purpose and technique to conducting.

However, much of it turns out to be non-intuitive. For example, neither tempo nor the temporal placement of the downbeat are perceived by musicians by following a beat pattern. Rather, both tempo and placement of the downbeat are communicated by the conductor (whether he or she is aware of it or not) according to how fast they breathe before the first downbeat. In fact, one of the typical drills at the school was to have conductors practice starting a piece using just their breath. It is amazing how necessary and sufficient breathing is for this part of the job, and how unimportant waving ones arms are.

Another example is that musicians respond to changes in tempo according to the width of the beat pattern, and not its actual period. Larger beat patterns make musicians slow down, and smaller patterns make musicians speed up. This is counterintuitive to what many conductors attempt in practice, which is to broaden their pattern in an attempt to speed up.

I agree that much of the work of a conductor is done at rehearsals. However, there is not a great deal of time to rehearse in the schedules of most professional orchestras, so the in-the-moment skills that leverage actual craft will always be at a premium.

Another significant thing conductors ought to do which nobody has mentioned yet is to balance dynamic levels. A good conductor in the case of, for example, a concerto should probably spend most of his or her effort getting the orchestra to play soft enough to allow the soloist to be heard.

Jeff rosner

Sat, 08/20/2016 2:35pm

I completely agree with the prior comment, with the exception that in performance the conductor acts as a nuanced metronome.

Emil Friedman

Mon, 08/08/2016 4:53pm

The conductor's main contribution is during rehearsals. That's where he or she teaches the orchestra what the piece should sound like and how to make it sound that way. That's also where he or she and the orchestra learn to understand each other. Following a video of an unfamiliar conductor without even hearing the rest of the orchestra sounds like an exercise in futility.

David Elaine Alt

Thu, 08/25/2016 12:56pm

Yes, most orchestral/band conductors also conduct with a "downbeat" that is really a setup for an upward bounce that coincides with the actually played downbeat.

This is improper technique, but it is way more common than beat one actually being a downbeat.

Your observation that no one comes in at the actually conducted downbeat reinforces the question of what are they following, if not the beat pattern?

Which is related to my comment above, which is that they are really following the breath of the conductor.

The most iconic lesson from the Monteux school was "One is down!" And it is surprisingly difficult to learn.

peter m herford

Wed, 08/24/2016 4:51pm

Conductors have varying downbeats. Some downbeat ahead of the first attack, some on the attack, and an occasional laguard. Personal style is the answer. Conductors vary in their downbeats from Leonard Bernstein who revelled in grand motion when the score permitted, to Karl Boehm whos economical conducting style did little more than hint at the downbeat.

The best story I know is the one about the guest conductor new to an orchestra that quickly discovered the lack of clarity in his downbeat. The downbeat came slowly, so thre issue was, where do we actually start?

Members of the orchestra got together and decided to create their own visual cue. The third button down on his jacket was their entrance. It worked and the conductor never figured it out.

Ishmael S-W

Mon, 08/22/2016 11:22am

"with the exception that in performance the conductor acts as a nuanced metronome."

I am sad that you think that way. Perhaps you have never had the experience of what could be a merely accurate rendition, turned into an exceptional musical performance by a conductor who knows how to play an orchestra.

Or as one singer said after a performance:

"While your leading style did not exhibit the wonderful flair some of our friends have, you did a lot more than simply `keep time'; your direction was intelligible and sensitive and very helpful."

--Robt. Dove, 2009.03.27

Allan MacLaren

Wed, 08/24/2016 8:42pm

Very Well said.

Allan MacLaren

Sat, 08/20/2016 7:54pm

Emil Friedman nails.

Stefan Lano

Sat, 08/20/2016 4:37pm

Emil Friedman is absolutely correct in his assessment. Having observed everything from the Democratic and Republican conventions to Boston Celtics games, it appears that in the USA, life has, indeed, become a movie. This movie cannot be translated to the world of symphonic music. The truly great conductors of the 20th century are names scarcely known in the USA: Fritz Busch, Erich Kleiber, Rudolf Kempe, Kurt Sanderling. None of them would have fared well in the MIT study, while the results of their work can still be admired today when such music-making has become too rare.

Vivek Dhawan

Mon, 08/22/2016 12:23am

Hi, I have a question, which I could google but you could answer - are there studies of effectiveness of sign language, is that a related area? and are they both related to the mirror neurons studied (and so eloquently discussed) by V. Ramachandran and others?

Stefan Lano

Sat, 08/20/2016 5:40pm

Emil Friedman is correct in his comment that the conductor's work is accomplished primarily in rehearsal. I see no point in the purported 'research' being conducted on the physical aspects of a conductor's gesture. What would these researchers have done with a Fritz Reiner, Kurt Sanderling, Fritz Busch or Günter Wand? MIT must not feel that it is obliged to explain every wonder of the human condition, least of all the inexplicable wonder of why some conductors are great and others not, as such is beyond empirical analysis.

Andy Del

Sat, 08/20/2016 5:22pm

As a conducting music major last century, my desire to progress to a Ph.D was in this exact field. Told to go do an undergrad in psychology...

A conductor's gestures convey a world of information. This study goes a ways to showing this, although I suspect much of what happens is a subconscious reaction on the part of the performer, AND an integrated, learned behaviour on the conductor's behalf.

Teaching in various areas of music is still very much master apprentice relationships, but no more so than conducting. Shame that... It would help our art if better training was available.

peter m herford

Sat, 08/20/2016 10:58am

M Platte was ill served by her high school, and the Media Lab does not seem to have any musicians on tap. Ask any conductor and the first words out of her or his mouth is: score study. The conductor, who is often an instrumentalist by training, studies the full orchestral score to the point where she/he knows the piece often by heart. As Emil Friedman points out, rehearsal is the key role of the conductor. It is hard to imagine the nonsense of this study. Have a look at Karl Boehm one of the great conductors of the Vienna Phil of the last century. there were long performance passages where he did not conduct. Daniel Barenboim and many other keyboard players often play Mozart and Bach in smaller orchestral groups by "conducting" from the piano. The musicians know the repertoire so well, they need little conducting. By contrast a guest conductor of a third or fourth tier orchestra may have to work extra hard to get the sound she/he wants. The conductor may then be a teacher more than a conductor. The arm movements are the least of what a conductor does..

Jan Wissmuller

Sat, 08/20/2016 9:44am

I scanned the thesis, but did not read it closely. Even within the self-imposed limitations of this sort of experimental work, I found one element unfortunately overlooked, and that is any research concerning the learning process. Even for something as comparatively simple as tempo conducting, my experience is that performers "learn" (quickly or slowly, dependent on both performers and conducting technique) a conductor's tempo conducting and become more accurate and less stressed over time. Experienced performers, who have learned several conductors in their careers, accomplish this learning much more quickly, etc, etc. Particularly since new and apparently inexperienced performers were used in parts of the testing, I would have thought that the evolution of their accuracy over the course of the experiment would be of particular interest.

Ray Jackendoff

Sat, 08/20/2016 9:38am

I have had the experience of playing with an orchestra, and one day a substitute conductor stepped in after several rehearsals with the regular conductor. And the orchestra sounded entirely different: more energetic and more expressive, thanks to the sub's gestural (and facial) communication.

Shahrukh Merchant

Sat, 08/20/2016 9:19am

With the caveat that I'm a music aficionado rather than a musician, I indeed agree with the previous poster. It's not that a passionate and charismatic conductor can't influence the way that the orchestra plays, or the audience's enjoyment of the performance, but it's just that it seems to be at best 5-10% of what a conductor does, while the underlying assumption of the article (one hopes not of the research itself) is that it's the essence of the conductor. It would be like evaluating a sports coach based solely on the effect of his sideline instructions and screaming during a game. I suppose that's why they've started calling them "musical directors" now.

Beyond that, assuming you have good musicians in the orchestra, it's hard to believe that the purity of their notes or their timing accuracy could be influenced by watching a video of someone "waving his arms better" (was there a control experiment done with a video of a metronome ticking?). It would be interesting to know what the "predefined musical/interpretational goals" were and how they were correlated with what an audience would perceive as a better performance.

As an outsider (i.e., performance spectator), it seems to be that during the performance (the part I get to see), the conductor inspires and creates enthusiasm that results in a more emotional performance OF THE ENTIRE ORCHESTRA (however you would measure that with sensors--facial expressions perhaps, assuming you don't want to plant electrodes in the listeners' and musicians' brains), rather than a mechanical-sounding one. But at an intellectual level I know that most of the conductor's work happened earlier, as I also do that there are "showman" conductors with exaggerated gestures that, if done well, can make the performance more entertaining for the audience (with the risk of seeming clownish if done poorly), but with unknown (to me) effect on the quality of the strictly audible portion of the performance (as might be evaluated by an audio recording).

David Eaton

Sat, 08/20/2016 8:42am

Leonard Bernstein believed that baton basics (the gestural aspect) could be taught in one coaching session, yet Max Rudolph wrote an entire book on the subject. But as Mr. Friedman correctly points out, the gestural aspect is but one aspect of the art. The conductor is the final arbiter of musical decisions with regard to phrasing, articulation, tempi, dynamics, etc. And yes, it's in the rehearsals where these issues are worked out in order to bring a unified realization of the score. We can point to conductors whose gestures are wooden, or limp, or crisp but turn out wonderful performances in spite of their gestural differences.

David Eaton

Sat, 08/20/2016 8:21am

Leonard Bernstein believed that baton basics (the gestural aspect) could be taught in one coaching session, yet Max Rudolph wrote an entire book on the subject. But as Mr. Friedman correctly points out, the gestural aspect is but one aspect of the art. The conductor is the final arbiter of musical decisions with regard to phrasing, articulation, tempi, dynamics, etc. And yes, it's in the rehearsals where these issues are worked out in order to bring a unified realization of the score. We can point to conductors whose gestures are wooden, or limp, or crisp but turn out wonderful performances in spite of their gestural differences. And if anyone can actually find the point of ictus in watching the hyper-twitchy Valery Gergiev, my hat's off to you. Yet, more often than not he gets terrific results.

P Chin

Sat, 08/20/2016 8:21am

Conductor-musician brain-to-brain correlation would be even more revealing.

This with portable non-invasive Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) tissue oxygenation monitoring.

This has been applicable to jet pilot "gravity-induced loss of consciousness" (GLOC) prevention and maintenance of consciousness, as well as medical and hospital applications.

...

P Chin

Sat, 08/20/2016 8:18am

Conductor-musician brain-to-brain correlation would be even more revealing.

This with portable non-invasive Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) tissue oxygenation monitoring.

This has been applicable to jet pilot "gravity-induced loss of consciousness" (GLOC) prevention and maintenance of consciousness, as well as medical and hospital applications.