How One Alum's Casual Chat Led to Pioneering Work in Ultrasound

-

-

slice.mit.edu

Filed Under

Recommended

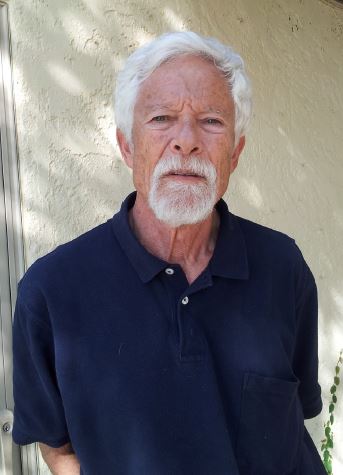

Roy Kopel '61, SM '63 owes much of his career to a casual two-hour conversation with an office mate about piezoelectric materials, which generate an electric charge when stressed. That chat, which happened in 1963 at MIT’s Instrumentation Lab a year after Kopel earned his Course 2 master’s degree, came in handy at a subsequent job interview.

“I’d seen an ad from Hewlett-Packard in Waltham, recruiting engineers for a medical ultrasound project, and thought it sounded interesting,” he recalls. “It turned out that medical ultrasound utilizes piezoelectric sensors, and the engineer interviewing me knew nothing about them. But I had a two-hour head start!”

Kopel got the job and the opportunity to learn about what was then the emerging field of ultrasound diagnostics. After Hewlett-Packard canceled the project, he applied his knowledge at a small industrial-probe company in Pennsylvania before moving to Arizona and joining Advanced Diagnostic Research (ADR), which was working on an innovation: moving ultrasound images.

“At the time, ultrasound machines were clunky monsters that could only make still images,” Kopel recalls. “I was in charge of probes at ADR; we developed the first compact real-time imaging systems and came up with enough innovations and patents to keep us in the forefront for several years.”

After ADR was sold to Squibb in 1982, Kopel and several colleagues founded Acoustic Imaging (AI), where his probe designs took another leap forward before the firm was acquired by Daimler-Benz.

“The initial real-time probes were flat and were good for obstetrics,” Kopel explains. “But we found that for general body or cardiac imaging, where bones get in the way, a curved probe has better imaging access. We started with a radius of 15 millimeters; almost as an afterthought we made some with about a 60-millimeter radius, and they became the most common type used today.”

The American Institute for Ultrasound in Medicine has honored Kopel as a pioneer, and his hand-built prototypes have been exhibited at the Smithsonian. But what he finds most satisfying is that ultrasound has proved so widely useful. Kopel notes that when he needed a scan recently, “the technician used a curved array and I thought to myself, ‘I made that!’”

Kopel lives in Arizona with Jemma, his wife of 28 years. An enthusiastic cyclist, he acknowledges that he’s slowed down a bit, but that’s a relative concept. “Nowadays I’m only riding two or three days a week,” he says, “and doing 2,000-foot climbs instead of 7,000.”