Hear the “Conlangs” Invented by MIT Linguistics Students

-

-

School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

Filed Under

Recommended

Wouldn’t it be great if there were an exclamation designed specifically to use when your cellphone battery runs out of juice? Or a word that perfectly captures the idea of doing something for no reason?

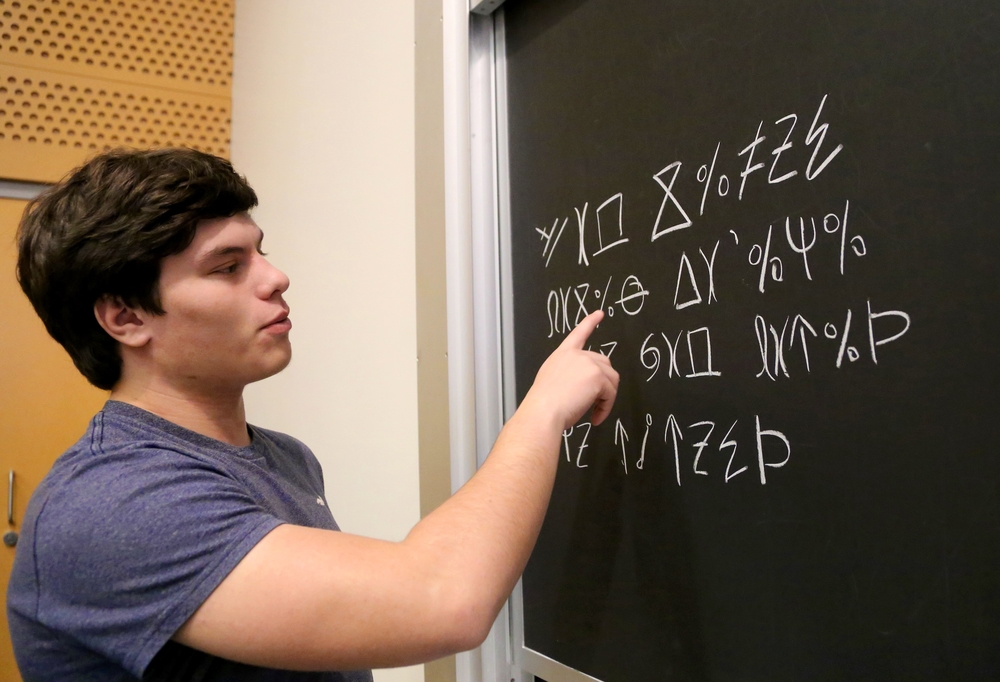

MIT students have been making up such words—but not for English, or any other known language. They are constructing entirely new languages—or “conlangs”—in a class that uses linguistics, the science of language, to supply the necessary building blocks.

One student, who took 24.917 Constructed Languages this fall, created a language for underwater creatures who speak in shades of color. Another invented a language that combines speech with whistling. Senior Jessica Tang’s new language is for spaceships that speak. “It’s not a super-logical premise,” she says, “but it’s a lot of fun facing the constraints. And I like a lot of the words in ‘spaceship-speak’ because they are just really weird.”

Beyond imaginative premises, the challenge students take on in 24.917 is to create something that behaves in ways that are fundamentally different from the language(s) they already know. To achieve that, it’s useful “to understand something about how human languages actually work,” says Professor Norvin Richards PhD ’97, a linguistic scholar who teaches 24.917.

Understanding how languages work is what the linguistics field is all about, and 24.917 provides a thorough introduction to the subject—including fundamental topics such as phonetics (making sounds), morphology (forming words), and syntax (developing phrases). The class, which debuted in 2018, has quickly become one of the most popular offered by MIT’s top-ranked linguistics program.

“One of the things you discover when you begin to learn about language is that there are all sorts of things that we do effortlessly, without thinking about it, but that are quite complicated,” Richards says. For example, English has quite a strict rule for ordering adjectives—it’s always “a big red car,” never “a red big car.” New English learners routinely have to memorize this far-from-universal rule, while native speakers may not even be aware of it.

“One of the goals of 24.917 is to show students some of what we know about how languages work thanks to all the work that’s been done in linguistics, which is the study of what exactly it is you know when you know a language,” Richards says.

When asked to elaborate, Richards explains, “There are certain kinds of linguistic tasks that people seem to invariably accomplish in the same ways, no matter what language they speak.” Linguists endeavor to explain why that is. “A working hypothesis is that part of being a human being is having the kind of mind that allows you to construct and use language in certain ways but not others,” Richards says. “We're trying to discover what those properties of the human mind are. What kinds of creatures are human beings?”

Read the extended version of this story on the MIT SHASS website.

Learn more about MIT Linguistics:

- The building blocks of linguistics

- David Pesetsky PhD '83 on linguistics and the human mind

- Kai von Fintel: decoding the meaning of language

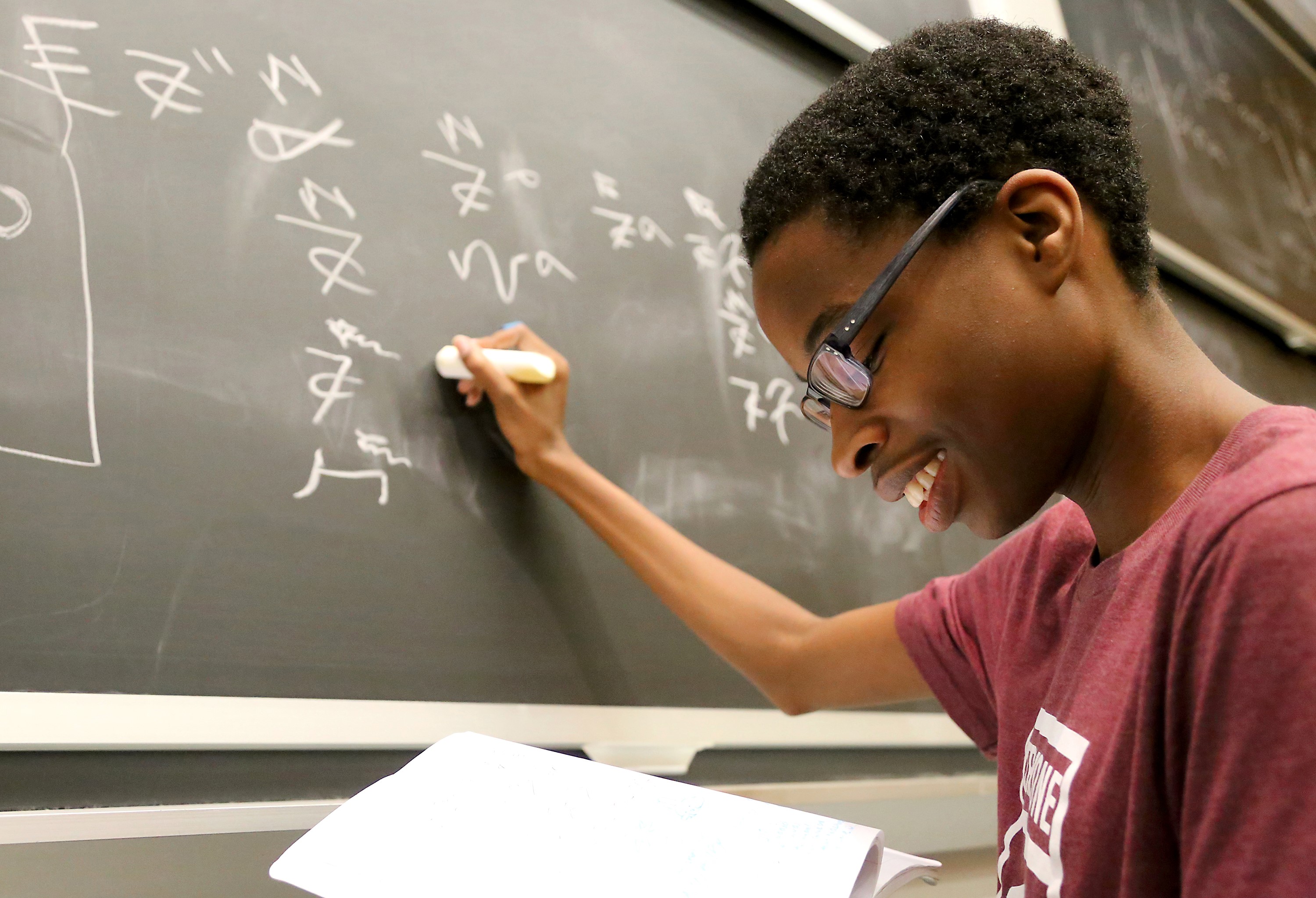

All photos: Allegra Boverman / MIT SHASS Communications. Shown at top: Tommy Adebiyi ’21 writes a sentence (roughly translated as "I wrote a piece of music") in his beat-boxing-inspired constructed language. Shown in thumbnail for audio feature: Alyssa Wells-Lewis ’21.