Forgotten History: Generators and the Gilded Age

-

-

slice.mit.edu

Filed Under

Recommended

If you’ve ever gone sightseeing in Boston, you probably spotted a unique piece of MIT history perched above the Charles River. Not sure what is? Here’s a hint: It booms and pops and can even make music. It’s the huge Van De Graaff generator (VDG) at Boston’s Museum of Science. Though the generator has long been on exhibit at the museum, it was first used for MIT research.

Invented in 1929 by Princeton’s Robert Van De Graaff, the generator uses a metal belt to accumulate electric charge on a hollow metal globe at the top of an insulated column and was used for research in early atom smashing and high-energy X-ray experiments. The invention caught the eye of Van De Graaff’s former Princeton colleague, MIT President Karl Compton. Compton insisted that Van De Graaff and his invention come to MIT. Van De Graaff arrived at MIT in 1931, as did a version of his generator, which found a home in Eastman Laboratories. But the version of the generator that would eventually end up in the Museum of Science was yet to be built. Compton had requested the largest Van De Graaff generator ever made—40 feet tall. To undertake such a massive project, Van De Graaff needed space, and he found it at MIT’s facility at Round Hill in, Dartmouth, MA—another often-forgotten piece of MIT history.

How MIT ended up with facilities in the tony part of Southeastern Massachusetts is a legacy from the gilded age. Colonel Ned Green, son and heir of “Witch of Wall Street” Hetty Green, built a

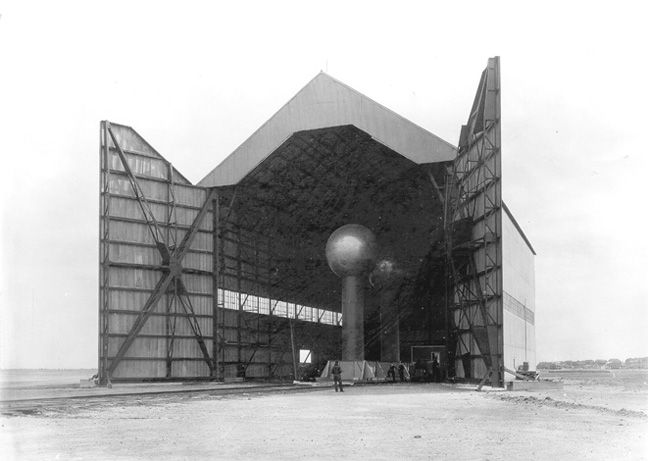

240-acre coastal estate in Dartmouth in 1916. With an avid interest in technology, Green complimented his estate with cutting-edge radio towers and broadcasting equipment. Green invited MIT students to use this equipment, study, and live on his estate—making it an ideal location to build the huge generator. The generator was built in an airship hangar on moveable tracks, and it was first tested in 1933. According to MIT President’s Reports, the generator was utilized in “experiments on atomic disintegration,” as well as for research into the “phenomena of lightning not heretofore investigated.”

The generator remained active in research at Round Hill for over 20 years—helping to facilitate experiments in nuclear medicine and radiography—until it was deemed obsolete and donated to the Museum of Science in 1956. The Round Hill estate, bequeathed to MIT by Green’s family in 1948, continued to be used for research until it was sold in 1964, ending the Institute’s experimentation at Round Hill.