Fifty Years of UROP Stories

-

-

MIT Technology Review

- 1

Recommended

Malcolm Best ’71

Dining with artistic icons Andy Warhol and Paloma Picasso wasn’t what architecture major Malcolm Best expected when he signed up for the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP) at MIT in the fall of 1969.

In fact, he didn’t know what to expect at all. He was one of 25 students to join the first year of the program, created by Margaret MacVicar ’65, ScD ’67, to give students the opportunity to pursue research with faculty mentors. These days, as it marks its 50th anniversary, UROP is a rite of passage for 90% of MIT undergraduates.

But back then, Best knew only that he had a question that intrigued him—“How could you use light in the way you use music?”—and that UROP offered hands-on work with architecture professor Friedrich St. Florian, who was exploring the uses of light. He began working with a group of fellow students on an installation St. Florian was creating for the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford. (Felicitous seating arrangements at the opening reception led to the Warhol/Picasso encounter.) Simultaneously, Best pursued an individual project to build a “color organ” that could be played to produce light of various hues.

In the era predating personal computers, it was primarily a mechanical challenge. He recruited half a dozen friends to help with the wiring. “The keys were sticking,” he recalls, “but we had other ways of driving it. One was using a plexiglass disc that rotated over photo cells and was shaded to produce different intensities of light.”

While the project tapped into Best’s maker spirit, its artistic premise fed his metaphysical leanings. At a time when his design and architecture classes championed the credo “form follows function,” he says, “I was more into symbolism and how architecture affects consciousness.”

After MIT, Best did graduate studies in social work and fine arts, trained in psychodrama therapy and Zen practices, and worked for several decades in computing (including as IT systems lead for the launch of bakery chain Cinnabon). In retirement, he has volunteered for sustainability causes in his longtime home of Seattle and taken up painting.

Best says it’s difficult to tease out the ways his UROP experience influenced his life. St. Florian—who later gained fame for his World War II Memorial in Washington, DC—was already eminent, in the way “everyone at MIT was eminent,” he quips. The star-studded Wadsworth exhibition makes a good anecdote. But what stays with him most was the camaraderie of building something with his peers. UROP “was unique in its scope and freedom,” he says. “I learned a lot more by those little failures than I did in my courses where they told us, ‘This is how you do it.’”

Something else has stayed with him all these years: the color organ. Although it never quite worked the way he’d imagined, “I still have a section of one of the light banks downstairs somewhere,” he says. “I used to bring it out at parties and plug it in.”

James Bellingham ’84, SM ’84, PhD ’88

Ask Jim Bellingham what he focuses on as director of the Center for Marine Robotics at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and he starts by saying the ocean’s critical role in climate change is poorly understood because the ocean itself is not yet well understood. Robotic technologies like the ones developed at Woods Hole will play a key role in unlocking that knowledge. They are changing how ocean science is done, he says, with major implications for the military and industries including aquaculture, even as robotics itself is rapidly transformed by advances in other technical fields, including machine learning, energy storage, and sensors.

As his answer shows, Bellingham is a big-picture kind of guy. Forty years ago, he gained his first big-picture view of science through UROP, courtesy of its founder. When Bellingham began a UROP in MacVicar’s physics lab, which specialized in research on superconductors, she had just begun a new electromagnetism project with Honeywell, assessing the feasibility of directly detecting what’s known as curl-free vector potential. The engineering and manufacturing company hoped to use the results for a communication system.

Spending two years on the project during his UROP, Bellingham grew to appreciate its complexity. He got to help tackle physics questions that are fundamental—even controversial, since there is no scientific consensus over whether the curl-free vector potential is a genuine field or just part of a mathematical construct. He worked on mathematical challenges and learned about new computational approaches to crunching the numbers behind what he wryly recalls as “horribly complicated theoretical solutions.” (Bellingham was among those tasked with doing the crunching.) And there were big meetings with visiting researchers, for which he’d pull all-nighters to photocopy thousands of pages, and then sit in the back of the room soaking everything up the next day. The central scientific question of the project, Bellingham notes, has yet to be resolved today. “There could be a Nobel Prize in that,” he says.

MacVicar, who became Bellingham’s PhD advisor and mentored him until her death in 1991, helped him appreciate the sprawl of scientific research. She walked him through the challenges of industry collaboration, which gained new relevance for him in 1997 when he cofounded MIT spinout Bluefin Robotics, which specializes in autonomous underwater vehicles. She gave him practical pointers, too. He remembers how she calmly stepped in during his first liquid helium transfer to turn a release valve and prevent a relief tube from bursting. The weekly reports he asks his own students to complete are a habit imparted by MacVicar. His unfailingly thorough preparation for even the simplest PowerPoint is a direct result of her relentless probing during his MIT presentations. “Margaret believed you needed to be pushed in a safe environment before you went into the real world and were roughed up by people who did not have your best interests at heart,” he remembers.

For Bellingham, UROP was its own release valve of sorts from the restrictions of a traditional curriculum. “In the classroom, you start out doing physics that was done a few hundred years ago,” he says. “You don’t get close to the frontiers of physics until grad school. Honestly, how are you supposed to know if you’re going to like this? Whereas UROP plunks you into the lab and makes you feel productive from day one. That was what told me I could see myself doing this for my career.”

M. Amah Edoh ’02, PhD ’16

As an MIT assistant professor of anthropology and African studies, Amah Edoh has advised two UROP students so far. For the first, whose project was primarily in engineering, Edoh focused on helping her think through questions of social impact and how she might use qualitative research methods. For the other, whose research was interview-based, “it was about how to craft a project that’s feasible and true to your interests.”

Edoh is passing on the type of guidance she received two decades ago, when she took multiple turns on the student side of the UROP relationship. Her first project was in mechanical engineering—“That was when I was still trying to make myself into an engineer”—but her subsequent three UROPs helped her realize that her interests lay in the humanities and social sciences.

“Being at MIT and realizing I didn’t want to be a STEM person put me in a very vulnerable place,” she says, crediting UROP for helping her to “find other spaces where I could satisfy my intellectual curiosity and explore topics I didn’t quite know where to find in my coursework … where I could feel like I was good at what I was doing, and what I was doing mattered.”

As a sophomore, Edoh lent her data-entry and language skills (her family is from French-speaking Togo) to history professor Jeffrey Ravel’s investigation of 18th-century French theater. For her next UROP, she assisted with the French-to-English translation of visiting professor Odile Cazenave’s book about Francophone African writers. Her final UROP supervisor, political scientist Melissa Nobles (now the Kenan Sahin Dean of MIT’s School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences), involved Edoh in her own research on the politics of social justice and advised her undergraduate thesis on an NGO in Ghana fighting to improve access to sanitation in cities.

Edoh’s UROP experiences would eventually connect to her career in several ways. After six years working in and studying public health, she returned to MIT, earning a PhD in the Program in History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology, and Society. Ravel, who is still on MIT’s history faculty, once again served as a mentor while she was a grad student. And Edoh’s strong identification with Cazenave’s work in African studies and cultural production (“I wanted to be her when I grew up,” she says) manifests in her current research: she is writing a book that traces how Dutch wax cloth produced in Holland became iconic as African print cloth in Togo.

Edoh says that beyond helping her discover her academic passions, UROP played another critical role in her education, one that influences her own teaching.

“My advisors were faculty members who really cared for my well-being and who were eager to be supportive,” she remembers. “Beyond seeing what research looks like or getting greater insight into a particular field of study, it really was this place where the faculty member could ask me ‘How are you doing?’ and get to know me over time. It’s about having a nurturing, sustaining relationship with professors during your college years, which is essential.”

This article originally appeared in the January/February 2020 issue of MIT News magazine, published by MIT Technology Review.

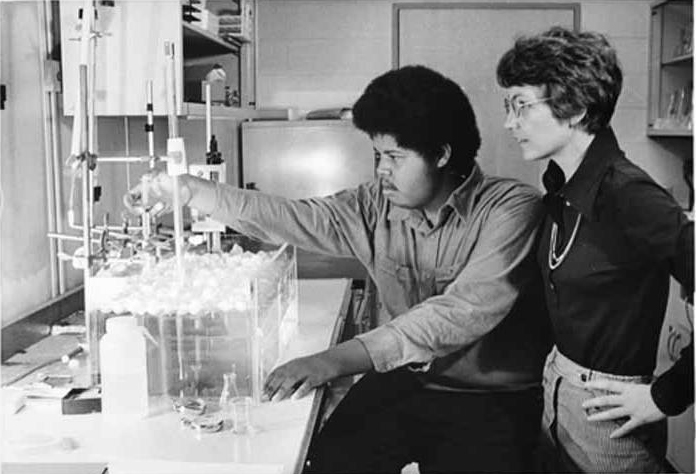

Photo (top): Margaret MacVicar, right, in 1979 with UROP student Miguel Mitchell '82. Credit: MIT Museum.

Comments

Thomas Jones

Wed, 03/26/2025 1:13am

UROP start date was earlier that 1969

I think i was in the first cohort to do research during the January 1967 January intersession. Perhaps it had a different name then. I was doing research on plasma chemical reactors under Professor Barbor. I completely changed my major and my whole approach to by career. It was one of the best experiences in my life.