Did You Get Anything Done Today? Thank Cognitive Control

-

-

Slice of MIT

- 1

Filed Under

Recommended

Many times each day you decide to do something—to cook a meal, perhaps, or to make a doctor’s appointment. And then, you do it.

In the gap between those two sentences lies one of the great mysteries of the human brain. No matter how mundane the “it” you’ve accomplished, what neuroscientist David Badre PhD ’05 really wants to know is: How did your brain steer you through all the tiny steps from thought to action?

“We mostly take our ability to get things done for granted and only notice it on those rare occasions when we struggle or fail. Yet, this ability is actually quite singular and marvelous, and also, unfortunately, quite fragile,” Badre writes in his new book, On Task: How Our Brain Gets Things Done (Princeton University Press). “The brain requires its own elaborate class of neural mechanisms devoted to generating plans, keeping track of them, and influencing a cascade of brain states that can link our goals with the correct actions.” That class of mechanisms is called cognitive control (also sometimes referred to as executive function), and it is the focus of Badre’s research.

We mostly take our ability to get things done for granted and only notice it on those rare occasions when we struggle or fail. Yet, this ability is actually quite singular and marvelous, and also, unfortunately, quite fragile.

A professor of cognitive, linguistic, and psychological sciences at Brown University, Badre says On Task is the first comprehensive overview of cognitive control for a general audience. It draws not only on his own research but a range of scientific literature. That includes accounts of what can happen when these fragile systems break down. In one drastic case described in the book, a brain tumor patient found post-surgery that it took him hours to work through the steps of even the simplest goals he set for himself, such as washing his hair. Complicated tasks and decisions became impossible, and the patient’s previously stable career and marriage quickly fell apart.

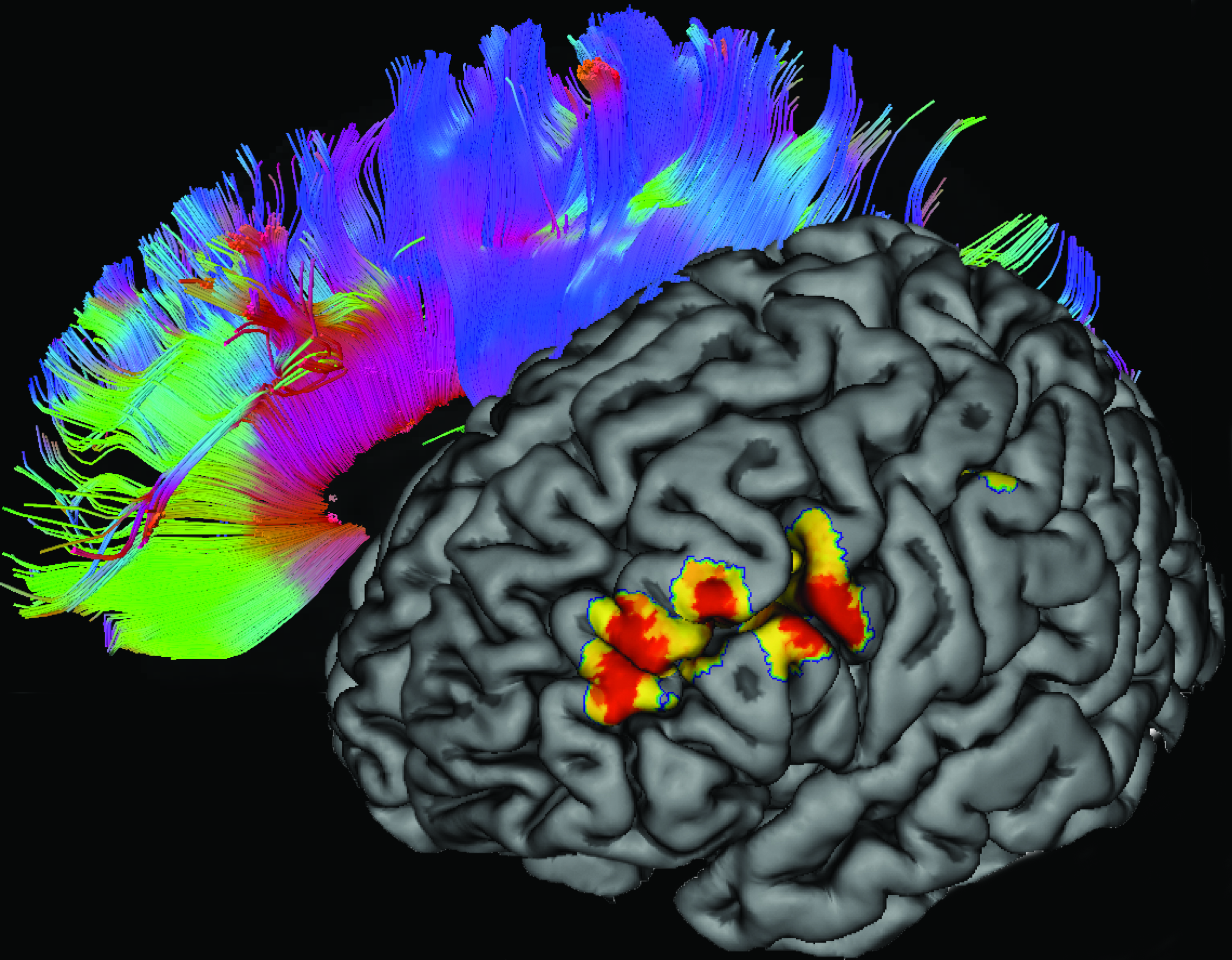

Despite such potentially devastating consequences when cognitive control is lacking, there is no scientific consensus on how it can be measured, let alone exactly how it works. Its entire purpose, Badre points out, is to enable us to operate in a messy, unpredictable world—the opposite of lab conditions. A typical study in Badre’s lab at Brown uses magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to record brain activity while subjects perform or switch between various tasks. Scaling up his group’s findings to the complexity of everyday life is the trickiest part of their work, Badre says. But doing so could pave the way for diagnostics and interventions to aid people with conditions that impair cognitive control, including Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s, and even the natural progressions of aging.

When Badre chose to major in biopsychology and cognitive science as an undergraduate at the University of Michigan, neuroimaging was just emerging as a scientific tool. “It felt like the telescope had just been invented. We were about to discover a frontier that had never been explored before, and that captivated me,” he recalls, “though we’ve since learned that it’s quite a bit more complicated than we thought back then.” He came to MIT to earn his PhD under cognitive neuroscience professor Anthony Wagner, whose lab studied learning and memory. But his research interests were also shaped by a class that applied engineering ideas about control to biological systems. “MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences has a long history of interdisciplinary thought,” Badre says. “They were among the first to really acknowledge that to understand the mind you have to also understand the brain, and to understand the brain requires drawing on a wide range of different influences.”

The people who think they are good at multitasking are the worst at multitasking.

Currently, Badre’s lab is investigating how different neural systems help us “gate” our working memory—in short, how we summon and act on the information most relevant to the task at hand. He is also studying how the different formats our brains use to store memories can affect how we control our behavior. Here, as with many aspects of brain function, Badre finds a useful analogy in the realm of computers. (The brain is not a computer, he is quick to note, but he does expect that discoveries in his field will buttress advances in artificial intelligence.) When our brains create and store a new memory, Badre suggests, it’s not so different from snapping a digital photo. Save the image in high-res, and you can zoom in on fine details or enlarge it without losing any of its crispness. But that large file size comes with disadvantages as well—cluttering up your hard drive, impractical to text or tweet. Likewise, our memories “trade off between very high- and low-dimensional formats, with different advantages for each.”

All of humanity’s mental strengths evolved with similar trade-offs, Badre says. This may spell disappointment for readers who pick up On Task for hot tips on how to juggle many tasks at once. Badre devotes a full chapter to how terrible our brains are at doing that. In fact, he writes, “the people who think they are good at multitasking are the worst at multitasking.” Practicing certain task pairings, or associating a task with environmental cues (like always writing at the same desk) may improve your efficiency a bit, but only as it relates to those specific tasks. Like many parents during the pandemic, Badre wishes he could “simultaneously check my child’s math homework while holding a meeting over Zoom,” but there’s a good reason why that’s not effective. “It's the price we pay for general cognition, the price we pay to be able to be as ingenious as we are,” he explains. General cognition allows us to quickly change our behavior in response to new situations. In a pandemic, for example, “We can suddenly change the way we shop, and the way we socialize, and the way we structure our day, almost overnight. That’s the plus,” he says. “The minus is that you’re building every one of those tasks out of the same building blocks. As a result, they’re going to interfere with each other and you can’t do them at the same time.”

Even so, Badre chose to end his book marveling at the enormous plus that is general cognition. It’s humanity’s unique capacity to adapt—not just across millennia or generations, but each of us within our own lifetime—that provides our collective best hope for addressing global crises like Covid-19 and climate change, he says: “We have this amazing ability not just to conceive of the way our society can be but to actually enact it, and we can do that because of cognitive control.”

Comments

Waqar Qureshi

Mon, 02/22/2021 2:26pm

Subconscious Decision Making

Great article. It would be very interesting to hear Professor Badre's thoughts on whether decision making is conscious or subconscious. If it's subconscious, as a lot of research suggests, then what does it really mean to say that "we summon and act on the information most relevant to the task at hand" or that "we can suddenly change the way we shop"? Isn't the entire process from making the decision to change the way we shop to actually changing the way we shop subconscious?