Bucky Fuller Dome that MIT Built

-

-

slice.mit.edu

Filed Under

Recommended

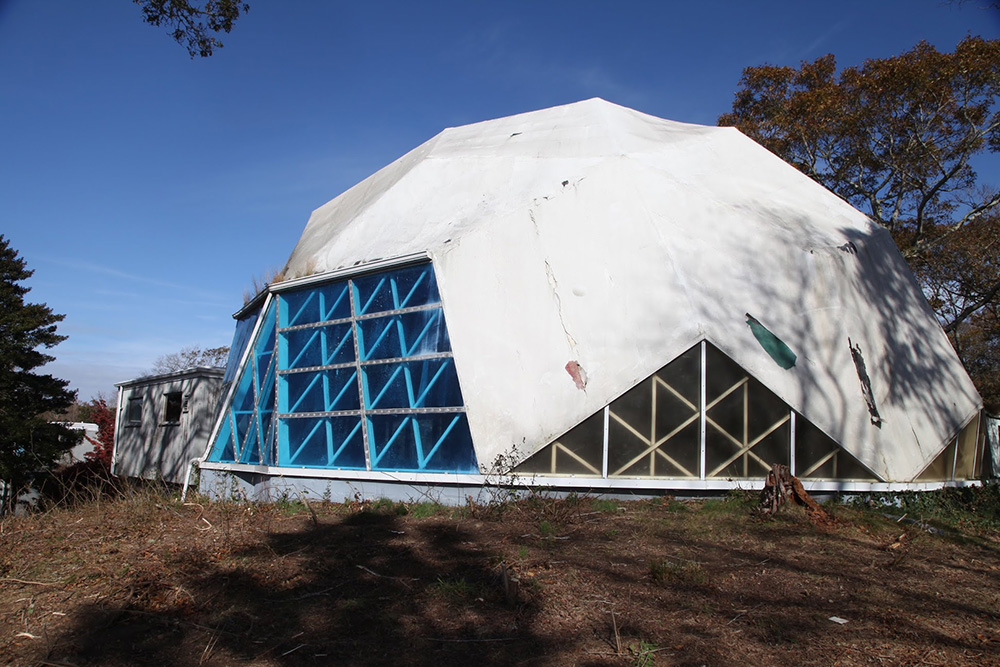

The oldest surviving wood-framed geodesic dome is easy to miss on the way into Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Built in 1953 by the renowned architect Buckminster “Bucky” Fuller and a group of students—many from MIT—the building served as the town’s popular Dome Restaurant for several decades. Over 65 years later, history has come full circle with a group of MIT alumni, students, and community members joining together again—this time to reflect back on the dome’s history and rehabilitate the now-dilapidated building for future use.

“I use that word ‘rehabilitate’ very deliberately because it’s a modern, experimental building,” said Bob Mohr MCP ’09, SM ’09, who is researching the building’s history as a member of the newly formed The Dome at Woods Hole nonprofit. They will draw on Fuller’s original intention to create a sustainable structure overlooking the Vineyard Sound that seamlessly connected the earth with water and sky, through a transparent roof.

“If anything happened to the dome, Fuller would want it to be innovative…and push the limits further into the future,” said Mohr. “Rather than trying to make it look like it did before, we start by asking what does it want to be.”

We need people dedicated to making buildings that are going to last hundreds of years and use as few resources as possible for the most gain.

Mohr interviewed many of the alumni now in their 90s that took part in building the dome. “I can feel their faces light up,” he says of his conversations. Among the builders were Tunney Lee, former department head for the MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning, and the late Peter Floyd MArch ’53 who went on to work with Fuller on other projects including Disney World’s Epcot Center.

Mohr has learned that the students pre-cut the wood framework in an MIT woodshop and transported it in one truckload down to the Cape. Actual construction took place over a period of weeks that summer. The building was later plagued with leaks, due to its rounded rhomboid panels. The transparent roof made for a hot, loud interior, especially because of the restaurant’s nightly zither performances. “The neighborhood went bananas,” said Mohr of the echo effect created.

While Mohr has focused on the dome’s history, MIT Professor John Ochsendorf and several of his students have analyzed its structure through 3-D modeling. “To me, it makes sense that MIT is involved, because Fuller was interested in innovation to make the world a better place,” said Mohr. “That’s what’s motivating us 100 percent.”

The actual rehabilitation may be several years in the future, but the nonprofit is committed to adhering to the sustainability tenets Fuller preached.

“We need people dedicated to making buildings that are going to last hundreds of years and use as few resources as possible for the most gain,” said Mohr. “That was what Fuller was about, and that’s what we think this place should be about too.”