Bringing the Margin to the Center

-

-

MIT Technology Review

Filed Under

Recommended

Today, one in every six people on Earth lives in an informal urban or squatter settlement. United Nations analysts estimate that number will rise to one in three by 2050. “Traditionally, policymakers see these people as a problem,” says Janice Perlman PhD ’71. “I believe they’re part of the solution.”

Perlman’s landmark 1976 book The Myth of Marginality invited readers to look at squatter settlements and shantytowns as potential assets, and at the people who inhabit them as a source of renewal for cities. “The goal is not simply improving living conditions in squatter settlements,” she says. “The goal is integrating the incredible energy and intelligence of the people living there in a way that benefits the entire city.”

Raised in New York in Queens and later Long Island, Perlman spent three months traveling South America with an American musical revue the summer after her freshman year at Cornell. The following summer she did fieldwork in fishing and agricultural villages in Bahia, Brazil. After she arrived at MIT in 1965 to pursue a PhD in political science, her dissertation research took her back to Brazil, where she and her team interviewed 750 subjects in three separate favelas—or shantytowns—in and around Rio de Janeiro. “I studied the impact of the urban experience on migrants who arrive from villages where they haven’t even seen a staircase,” says Perlman. Her research—which would eventually evolve into The Myth of Marginality—attracted the attention of Brazil’s military government; she says she was accused of being an “international agent of subversion” and had to flee the country to avoid arrest.

Perlman joined the faculty of City and Regional Planning at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1973 and received tenure five years later. She left in 1985, and two years later, in New York, she founded the Mega-Cities Project—a global nonprofit designed to shorten the lag time between ideas and implementation in urban problem- solving. “I don’t like the term ‘knowledge transfer,’” says Perlman, who soon created fieldwork teams in 18 cities, including Tokyo, Mexico City, London, Calcutta, and Lagos. “Knowledge transfer can work between high-level consultants or in academia. But no knowledge transfer can help you comprehend and collaborate with a person you see as the other. This is a transfer of know-how. A network of cities sharing common problems who collaborate to overcome obstacles, navigate government, and speed up changes in policy and practice.”

No knowledge transfer can help you comprehend and collaborate with a person you see as the other. This is a transfer of know-how. A network of cities sharing common problems who collaborate to overcome obstacles, navigate government, and speed up changes in policy and practice.

Know-how flowed freely as the Mega-Cities Project got off the ground. Developing regions shared solutions with developed regions and vice versa. New York tested aspects of a surface metro bus system from Curitiba, Brazil. Collaborators in Manila and Mumbai adapted a program invented in Cairo where workers sorted through refuse for materials they could convert into sellable art and craft objects. And São Paulo adopted New York’s City Harvest, which picks up unused food from restaurants and markets and distributes it to soup kitchens.

While Mega-Cities still exists, much of its funding and personnel were absorbed by the UN in 1999. But Perlman has been anything but idle. In 2010, she won a Guggenheim Award for her book Favela: Four Decades of Living on the Edge in Rio de Janeiro. She is currently at work on a third book, about the displacement and dispersal Rio’s favela population suffered during that city’s 2014 FIFA World Cup and 2016 Olympics. Last year, she received a Fulbright US Scholar Award to return to subsistence fishing villages outside the Brazilian city of Recife where she had organized a US-Brazil student project in the summer of 1965.

Perlman says she never had a “conventional job” after leaving Berkeley. “But it was a good decision that opened the door to a wonderful career that was much more satisfying than the one I’d have had if I’d stayed in academia,” she reflects. “I have no regrets.”

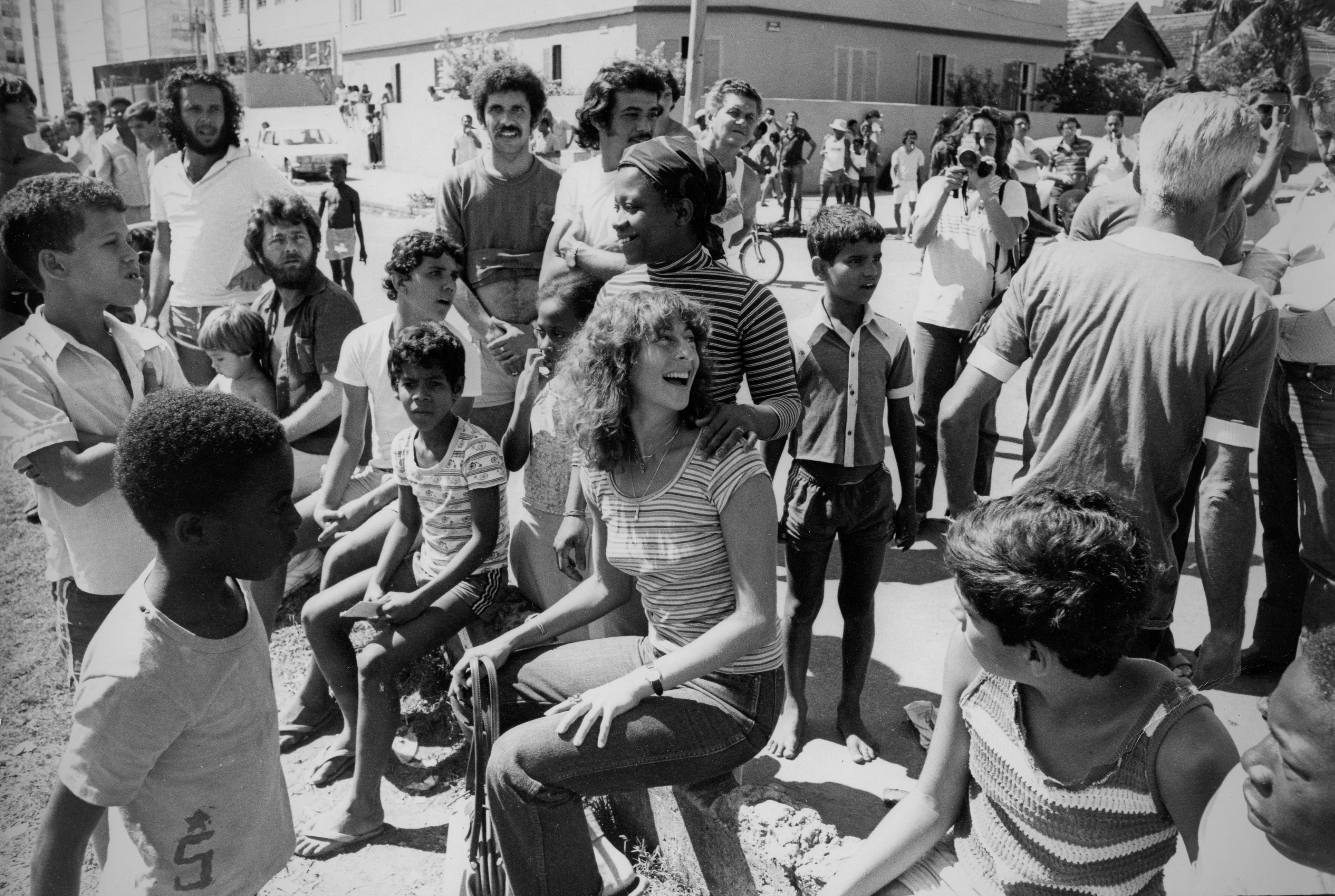

Photo at top: Perlman (seated at center), in 1973, with residents of Rio de Janeiro’s Conjunto de Quitungo Housing Project.

This story also appears in the November/December issue of Technology Review's MIT News magazine.