Becoming Part of the MIT Universe

-

-

MIT Technology Review

Filed Under

Recommended

In 1969, Michael Fant ’73 was sorting through a pile of college acceptance letters, trying to figure out which school to choose. So he returned to the segregated high school he’d attended for two years in Memphis, Tennessee, to consult with his favorite science teacher. “You got into MIT?” his teacher said. “That’s where you’re going. I don’t care if you have to borrow every penny.”

It was “huge” for somebody from his neighborhood to get into MIT at that time, says Fant, a retired neonatologist and physician-scientist known for his pioneering research in placental biology. “I wasn’t even sure I belonged there. It wasn’t so much about race as it was about the mythology associated with MIT, like it was a different universe. But one thing my MIT experience taught me was that I could be part of that universe. And I think my being there helped the Black students who followed me believe they could be part of it too.”

At MIT, he explored his interest in medicine in the Department of Nutrition and Food Science. “We studied toxicology, nutritional biochemistry and metabolism, and global malnutrition,” he says. “I came to appreciate the impact of malnutrition during critical periods of growth and development. And this angered me, because the impact was borne primarily by people of color.”

After MIT, Fant entered a joint MD-PhD program at Vanderbilt University and joined a lab studying how drugs cross the placenta to the fetus. The first African-American to receive a PhD from Vanderbilt in the biomedical sciences, he went on to a prestigious clinical and academic career that included faculty appointments at Harvard Medical School, Washington University in St. Louis, and the University of Texas McGovern Medical School in Houston. He was ultimately recruited to the University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine, where he helped develop the neonatal research program and directed the neonatal-perinatal fellowship program before retiring in 2019.

Fant’s most notable research contribution is his work on a gene called PLAC-1, which is found on the X chromosome in the developing embryo and expressed primarily in the placenta. His lab was the first to demonstrate that the gene is essential for both normal placental development and brain development. “There is still so much research that needs to be done,” he says. “But at least we got this work across a critical threshold. And what a privilege it was to wind down my career with a contribution like this.”

This story also appears in the January/February issue of MIT Alumni News magazine, published by MIT Technology Review.

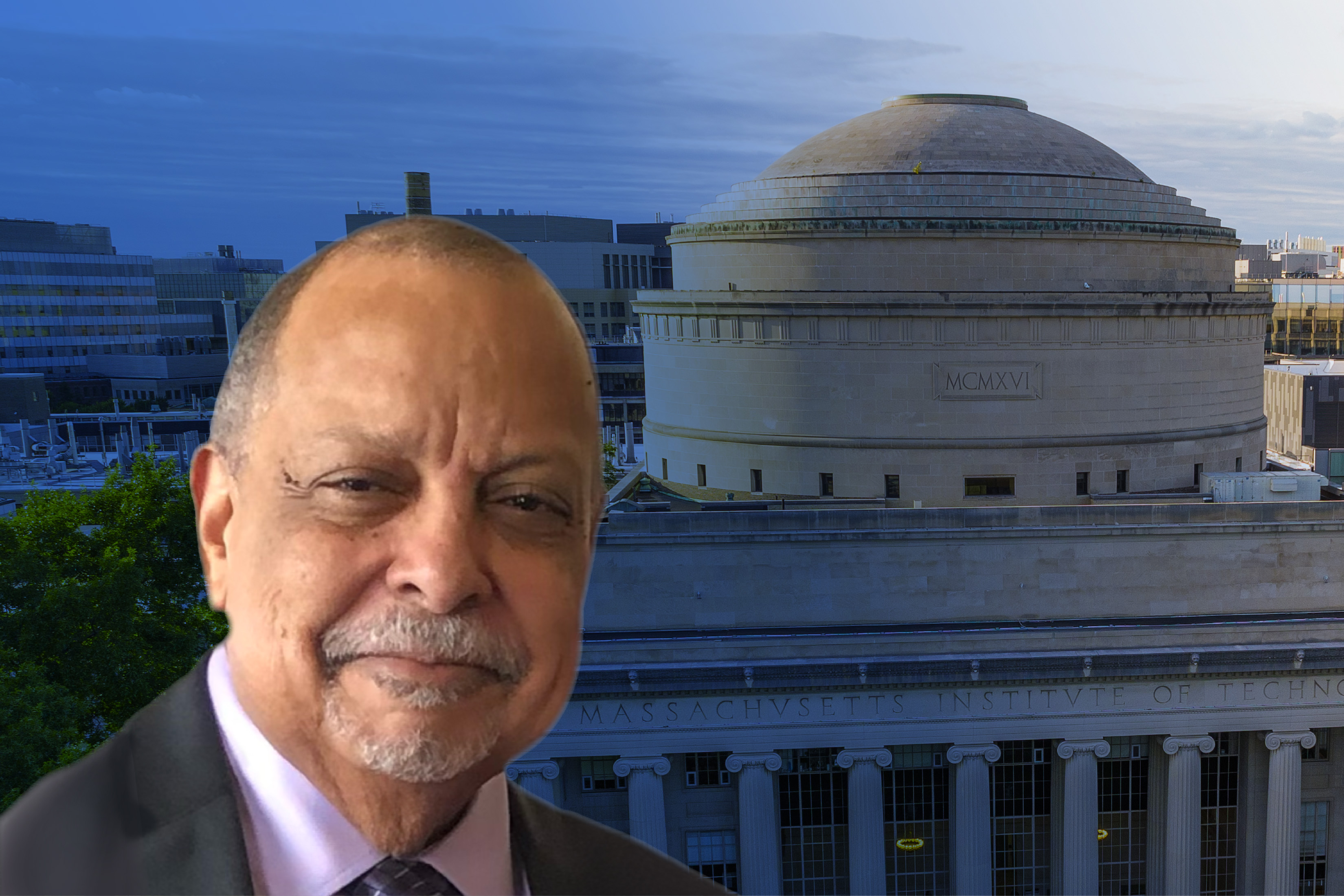

Photo illustration by Gretchen Neff Lambert; portrait image courtesy of Michael Fant; MIT dome image by Emily Dahl