10 Things You May Not Know About... Exoplanets

-

-

slice.mit.edu

- 3

Filed Under

Recommended

Background

As many alumni probably know, an exoplanet is a planet outside of our solar system that orbits a star other than the sun. Speculation about exoplanets has existed for centuries, with one of the earliest known references dating to the sixteenth century when Giordano Bruno, and Italian philosopher, put forward the view that fixed stars could be similar to our sun and likewise accompanied by their own planets. In 1988 the first exoplanet was detected.Today, astronomers have confirmed detection of 529 such planets, and more than 1200 additional planets await confirmation. The vast majority of these exoplanet candidates were discovered as part of NASA's Kepler mission, which launched in 2009 with the goal of locating Earth-size planets in Earth-like orbit around sun-like stars. MIT's Sara Seager, the Ellen Swallow Richards Professor of Planetary Science and Professor of Physics, is on the Kepler team, which recently released a slew of data to the public. Seager gave a talk about exoplanets on February 9 and touched on several of the points below.

10 Things You May Not Know About Exoplanets

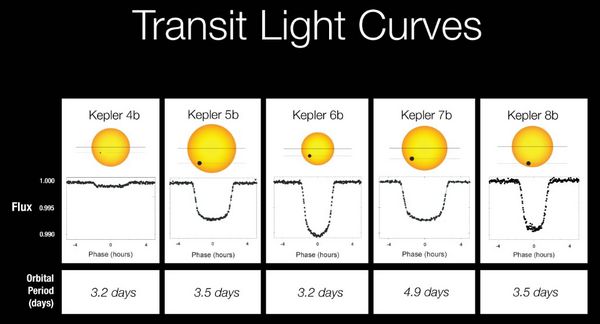

(as of February 2011)- The Kepler space telescope detects exoplanet candidates by looking at one large area of the sky and measuring the brightness of more than 100,000 stars every 30 minutes. Tiny "winks" in star brightness (which can last anywhere from an hour to half a day) occur when a planet passes in front of the star. This is called the "transit method" of detection. See Occultation-Graph animation (QuickTime, 1 MB).

- Exoplanets are confirmed by observing several transits that have the same dip in star light, time to transit the star, and amount of time between successive transits. It takes about 1000 people-hours to confirm an exoplanet.

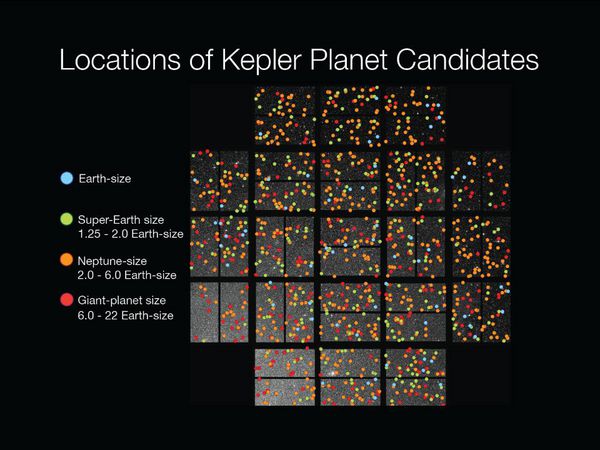

- Before Kepler, there were a total of about 520 known exoplanets, but last year the Kepler team announced 700 new exoplanet candidates, and in early February 2011 they unveiled 500 more.

- Of the 1235 exoplanet candidates identified by Kepler to-date, 54 are in the habitable zone (the region where water can exist as a liquid on the surface of a planet), and five are near Earth-sized. The five near Earth-sized planets orbit small, low-luminosity stars that are very different from our sun. The remaining 49 habitable zone candidates range from super-Earth size (up to twice the size of Earth) to larger than Jupiter.

- About 60 to 80 percent of the 1200 Kepler candidates are considered likely to be real planets.

- Professor Seager calls Kepler-11, which was revealed in the recent batch of Kepler findings, "the most fascinating planetary system ever discovered." Kepler-11 has six confirmed transiting planets, five of which are so close to one another that they gravitationally perturb each other's orbits, enabling scientists to calculate each of the planets' masses--and with additional Kepler data--their densities. Seager says the planets' densities are so low that they probably have low-density material like gas or ice in layers above any rocky/iron interior, making the Kepler-11 planets "unlike any planet in our own solar system." View an animation of Kepler-11 below: [vodpod id=Video.5546630&w=425&h=350&fv=%26rel%3D0%26border%3D0%26]

- Kepler-10b, also discovered recently, is Kepler's first confirmed rocky planet outside our solar system. It is 1.4 times the size of Earth, with a mass 4.6 times that of Earth and an average density of 8.8 grams per cubic centimeter--similar to that of an iron dumbbell.

- According to Seager, Kepler is single-handedly changing exoplanet science "from studying individual objects to studying the statistics of a large number of planet candidates."

- After exoplanets in habitable zones are identified, the next step is to detect light directly from the planets. Light spectrums help scientists determine what type of atmosphere a planet has and whether or not it could support life. NASA's Space Interferometry Mission and the James Webb Space Telescope both support these capabilities.

- Professor Seager encountered resistance when she was first applying for faculty positions because many major universities "didn't think exoplanets would be a real thing," she said at her talk last week. Now at MIT, Seager's research focuses on computer models of exoplanet atmospheres, interiors, and biosignatures. She has been awarded the Bok Prize in Astronomy from Harvard University and the Helen B. Warner Prize from the American Astronomical Society.

Comments

David Atlas

Sat, 07/25/2015 11:02am

I have been very excited by the finding of the exoplanets. As an MIT D.Sc.in metteorology

A I'm proud of Sara Seger's role in these discoveries. I have also done my best to present a lecture on this subject to our S&T Colloquia at our retirement community. If you read the news item mentioning Stephen Hawkings you will have learned that he believes (as I do) that there is a high probability of livable planets. Too bad that we are fouling up Eartth.

All the best.

David Atlas

Former Director of Earth Sciences at NASA Goddard

Bill Hobbins

Wed, 01/16/2013 11:38pm

How do I get involved?! I'd like to know!

Ron

Tue, 02/15/2011 5:41pm

Dear Dr. Seager,

Do I understand correctly that none of these planets are likely to support human life? I don't think we would survive under 5 G's on that Iron Planet!

Ron B