Happy 60th Birthday to the Word “Hack”

-

-

slice.mit.edu

- 2

Filed Under

Recommended

The modern definition of the word "hack" was first coined at MIT in April 1955. Photo by Nancy Crosby.

According to Wired magazine, the meaning of the word “hack” has been evolving for more than 500 years. Definitions include its earliest known usage in Middle English—“to cut with heavy blows in random fashion”—and its MIT-specific form— “mischief pulled off under a cloak of secrecy or misdirection”—that includes, but is not limited to, a stolen canon and a disrupted football game.

But the more broad definition of hack, commonly associated with disrupting technology, was also coined at MIT and quietly first appeared in the minutes of MIT’s Tech Model Railroad Club (TMRC) 60 years ago on April 5, 1955.

“Mr. Eccles requests that anyone working or hacking on the electrical system turn the power off to avoid fuse blowing.”

Mr. Eccles refers to William Eccles ’54, SM ’57, a then-MIT graduate student and member of the railroad club. In a 2014 post on the website trainorders.com, Thomas Madden ’59 elaborated on Eccles’ involvement.

“‘Hacks’ was the term applied to all manner of technology-based practical jokes at MIT, such as thermite welding a stopped trolley car to the tracks on Massachusetts Ave. I believe TMRC member Jack Dennis ’54, SM ’54, ScD ’58 is credited with applying the term as we now use it, but he was certainly abetted by fellow graduate student and roommate Bill Eccles.

“I remember each of them shouting 'Hacker!' in the club room whenever someone did something questionable—and they were particularly quick to shout it at each other. Often for no reason.”

And while many of the timeless MIT pranks that predated 1954—like gags on the old East Campus dorm in the 1930s or the Dipsy Duck in the late '40s—are now known as hacks, Madden doesn't recall that monicker during his time at MIT.

"Back then, I don't remember calling them hacks," he told Slice of MIT. "The were just practical jokes, or basically, things that you did and hoped you wouldn't get caught."

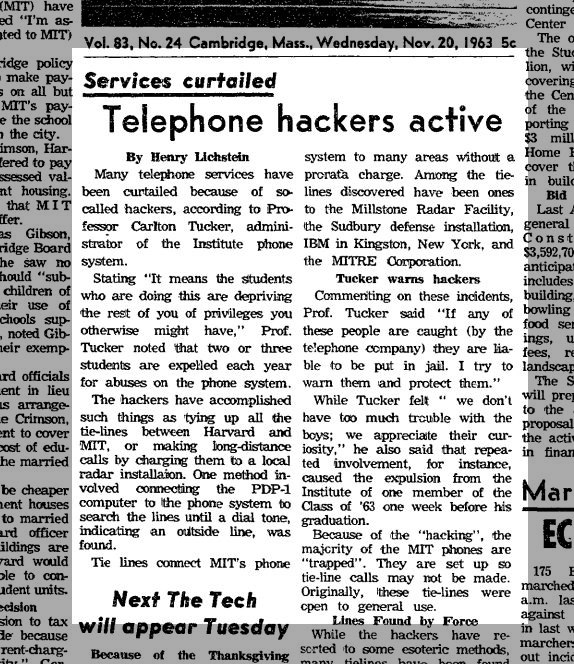

The first known mention of computer hacking occurred in a 1963 issue of The Tech.

And for good measure, according to wordorigins.com, the first known connection between the hackers and computing also occurred at MIT, in a November 20, 1963, article in The Tech.

“Many telephone services have been curtailed because of so-called hackers, according to Profess Carlton Tucker…The hackers have accomplished such things as tying up all the tie-lines between Harvard and MIT, or making long-distance calls by charging them to a local radar installation.

"One method involved connecting the PDP-1 computer to the phone system to search the lines until a dial tone, indicating an outside line, was found…And because of the ‘hacking,’ the majority of the MIT phones are ‘trapped.’”

Hack isn’t the only world that hatched for the TMRC’s unique jargon. The club created released own dictionary beginning in 1959 and TMRC-spawned words like “foo,” “mung,” “frob,” and “cruft” are familiar words in the lexicon of computer programming.

Read more about the Tech Model Railroad Club in 2012 article in MIT Technology Review magazine.

Comments

Larry Constant…

Thu, 04/30/2015 8:11am

Legendary hacker Dave Hahn, '65, was memorialized in my first novel (Bashert) for his stunt that sent the first morning train into Kendall Square Station skidding half-way across the Longfellow Bridge. Hahn died young but lived large, having started the storied club The Boston Tea Party and the first rural bus service in Belize. He was proud to be a hacker, and I was proud to have briefly joined him as a fellow member of HackComm in the '60s.

--Larry Constantine, '67 (pen name, Lior Samson)

Michael Hawron

Tue, 04/07/2015 5:13pm

Hacks! -- Or Applied Science; i.e Applied with Mischief -- April 7, 2015

The MIT Alumni website is wishing the word “Hack” its 60th birthday this year, so that makes us contemporaries, although I did not meet Hack until I was 18. The Concept of Hack makes more sense if you can fully appreciate the collective angst of thousands of clever, frustrated students surrendering their childhood freedom to the rigors of adult studies. At MIT, true release comes only from the cleverest form of mischief, be it on a grand or minuscule scale. On the grand scale you get phenomenon such as the sight of a full sized fire truck atop the great dome. [Great hacks are best pulled off under the cover of darkness.] There are considerable challenges involved in getting unwanted items to the top of the 150 foot high dome, but after all, this is Engineering Mecca.

On the minuscule end of the hack spectrum, as a freshman, I climbed to the top of that dome one night on the strength of a dare and greatly enjoyed the view thus afforded. The fun ended when it came time for the descent, when it became apparent that gravity was wont to accelerate objects over the edge to the awaiting abyss of the Killian Courtyard the equivalent of 15 stories below. The challenge was to provide enough friction to slow the descent without losing all of one’s epidermis. Obviously I was successful as I live to tell the tale this day.

-- Michael Hawron 1974